여학생의 신체활동 참가 촉진요인과 저해요인의 가설적 모델화를 위한 해외사례 종합 분석

A comprehensive analysis of foreign cases for hypothetical modeling of facilitating and hindering factors of girls’ participating in physical activity

Article information

Abstract

목적

본 연구의 목적은 여학생들에게 활발한 신체활동이 중요하다는 기본 전제를 바탕으로 여학생들의 신체활동 증진을 위한 가설적 모형을 구축하는 것이다.

방법

체계적 문헌분석 방법에 근거하였으며 2005년부터 2016년까지의 여학생 신체활동 촉진요인과 저해요인이 명시된 해외 연구 26편을 대상으로 분석하였다. 맥락별 요인 분류, 범주별 개념화 후 범주 간 관계를 도식화 하여 모델로 구성하였다.

결과

여학생의 신체활동 촉진요인은 일곱 개 요인으로 SPORTS로 명명되었다. ‘자기인정(지)(Self-Recognition)’, ‘물리적 환경(Physical Environment)’, ‘기회(Opportunities)’, ‘관계형성(Relationship)’, ‘적합성(Treatment)’, ‘사회적 지지(Social Supports)’이다. 이와는 반대로, 여학생들의 신체활동을 저해하는 요인은 총 아홉 개로 INCAPABLE로 명명되었다. 구체적으로 ‘내면화된 시선(Internalized Gazes)’, ‘부정적 피드백(Negative Feedback)’, ‘경쟁성(Competitiveness)’, ‘대체활동성(Alternativeness)’, ‘위험성(Perceived Danger)’, ‘외모(Appearance)’, ‘불쾌한 감정(Bad Feeling)’, ‘기회 부족(Lack of Opportunities)’, ‘여성적 규범(Effeminate Norms)’으로 세분화되었다.

결론

여학생들이 신체활동을 주체적으로 해석하는지 타인의 평가에 종속되어 대상화되는지에 따라 신체활동 양상이 달라지며 여학생들의 주체화를 증진하기 위한 개인적, 관계적, 환경적 차원에서의 노력이 필요함을 시사한다.

Trans Abstract

Purpose

The purpose of this study was to develop a comprehensive model for facilitating and hindering factors about girls' participation in physical activities.

Methods

Based on systematic analysis, 26 foreign journals published from 2005 to 2016 were comprehensively analyzed. The journals were directed to facilitating and hindering factors of girls' physical activities. A model was developed by categorizing various factors in the previous studies, and by conceptualizing those categories, and by creating visualization of relations between the categories.

Results

Seven facilitating factors are referred to as 'SPORTS', including ‘Self-recognition’, ‘Physical environment’, ‘Opportunities’, ‘Relationship’, ‘Treatment’, and ‘Social supports’. In contrast, nine hindering factors are conceptualized as 'INCAPABLE' which includes 'Internalized gazes’, ‘Negative feedback’, ‘Competitiveness’, ‘Alternativeness’, ‘Perceived danger’, ‘Appearance’, ‘Bad feeling’, ‘Lack of opportunities’, and ‘Effeminate norms'.

Conclusions

It is suggested that the girls' physical activity patterns vary depending on whether the girls subjectively interpret the physical activity or girls are being objectified by other's evaluation. And those individual, relational, and environmental levels are needed to strengthen the subjectification of girls.

서론

신체활동 증진은 체육학의 모든 분야가 몰두하는 핵심 주제다. 어떤 요인 때문에 사람들은 신체활동을 할까? 반대로 어떤 이유로 사람들은 신체활동에 참가하지 않거나 못할까? 체육학이 그 이론적 지형을 구축하기 시작한 시기부터 많은 연구자들은 이 질문을 고민하였다. 이 고민을 중심으로 체육학은 지금까지 아동에서부터 노인에 이르기까지 계층과 학력수준, 성별, 거주지와 신념 등의 다양한 변인에 따라 신체활동 참가 양상이 어떻게 변하는가를 이론화하고자 노력하였다.

이러한 노력에 있어 특히 청소년기 여학생은 특별한 대상으로서 주목받아 왔다. 신체활동을 향한 남학생의 적극성과 달리, 여학생은 우리 사회의 규범이나 제도, 관습으로 인해 신체활동에 소극성을 보여주기 때문이었다(Beltrán-Carrillo, Devis-Devis, Peiró-Velert, & Brown, 2012). “생물학적, 환경적, 사회적, 심리적 측면에서 신체활동 변화에 중대한 영향을 미치는 변환기(Eime, Harvey, Sawyer, Craike, Symons, Polman, & Payne, 2013, p. 158)”인 청소년기의 습관화된 신체활동이 전 생애에 걸쳐 형성될 체력수준과 성인기의 활기찬 삶으로 이어지기에(Halla, Victora, Azevedo & Wells, 2006; Kirk, 2005; Sallis & McKenzie, 1991), 여학생의 신체활동 증진은 모든 노력의 우선순위에 놓여야 할 정도로 중요하다.

이러한 중요성으로 인하여 지금껏 다양한 차원에서 여학생의 신체활동 증진을 위한 학술적 노력이 이루어졌다. 그 노력은 크게 네 가지 축으로 정리된다. 첫 번째는 기본 ‘인식’과 관련된 연구의 축이다. 이는 여학생이 체육수업과 신체활동을 어떻게 인식하는지를 묻고, 그에 따른 참여 실태를 종합하는 연구로서(Han, 2010; Hwang & Hwang, 2013; Kwag & Cho, 2015; Yu & Kim, 2002), 여학생들이 왜 체육을 부정적으로 대하는지(Yoo, 2002), 무엇이 체육수업 참여를 촉진 및 저해하는지(Hong & Lee, 2008; Lee, 2010; Lee, 2011)가 중점적으로 다루어졌다.

두 번째 축은 여학생들이 신체활동으로 얻을 수 있는 신체적, 심리적 효과를 밝히는 노력이었고(Lee, 2010; Lee, Kim & Moon, 2008; Nam, 2012), 세 번째 노력은 여학생들이 얻을 수 있는 여러 효과를 도모하고자 다양한 수업 모형과 전략을 활용하는 체육 활동 참여 방안 모색이었다(Jo, 2013; Kim & Lee, 2008; Ryu, 2014; Lee & Park, 2012). 마지막으로는 전술된 다양한 실천이 실현되도록 법제도의 기틀을 마련하는 노력으로서, 미국 Title IX에서 시사점을 얻어 여학생 신체활동 활성화를 위하여 국내 법제도를 마련하고 정책방향을 제시하는 시도였다(Jin, 2017; Joo, 2015; Kim, 2014; Lee, 2015; Nam & Lee, 2005).

지금까지 이루어져왔던 이러한 학술적 노력은 여학생의 신체활동에 방해가 되었던 일차적 진입 장벽을 어느 정도 허무는데 상당한 기여를 하였다. 특히 지금껏 학교 운동장에서 ‘신체활동의 모퉁이화(化)(Nam & Lee, 2006, p. 443)’를 체화했던 여학생들에게 인지적, 물리적 공간을 마련해줌으로써 신체활동 참여에 적극적일 수 있도록 사회문화적 분위기를 조성했다는 점도 지금까지의 노력이 남긴 긍정적 결과라 할 수 있다.

또한 정책적으로도 여학생 신체활동 활성화를 위한 노력은 꾸준히 이루어져 왔다. 학교체육진흥법 내 여학생 체육활동과 관련된 규정 신설과 함께 남녀분리수업, 여학생 선호종목을 담은 ‘2016년도 여학생 체육활성화 추진계획’ 등이 대표적이다(Ministry of Education, 2016). 하지만 이러한 정책은 여학생 체육활동 활성화에 필요한 기본지침을 기술하는 것에 그쳤다는 평가(Jung & Kim, 2016)를 받았으며, 이러한 노력에도 불구하고 여전히 여학생들의 상당수는 신체활동에 참여하지 않거나 못하는 상황이다(2015년 59.2%, 2016년 35.7%)(Ministry of Culture, Sports and Tourism, 2016). 실제 초·중·고교생 가운데 규칙적인 체육 활동에 참여하지 않는 여학생의 비율(49.9%)이 남학생의 비율(25.3%)보다 두 배 가까이 높은 상황(KBSnews, 2018.02.17)은 여학생이 좋아하는 활동을 제공하면 참여할 것이라는 단순한 정책적 논리가 현실에서 적용되기 힘들다는 것을 보여준다. 여학생의 신체활동 활성화를 위해 특히 사회문화적 차원의 이해가 학술적 차원 뿐 아니라 정책 수립 과정에서 부족했음을 보여준다.

신체활동 참여율이 낮은 현상에는 여러 원인이 있겠지만, 가장 큰 이유는 여학생 신체활동을 둘러싼 시간적, 물리적 조건의 명확한 이해가 선행되지 못했다는 데 있다. 그 조건을 마련하는 일은 여학생들이 신체활동을 하는데 무엇을 원하는지, 무엇을 원하지 않는지에 대한 요인을 분석하고 구조화하는 일에서부터 시작될 수 있다. 진입 장벽이 없다고 자발적으로 참여가 이루어지는 것은 아니기 때문이다. 이를 위해서는 여학생들의 신체활동 맥락을 구성하는 사회문화적 요인들을 살펴보고 사춘기라는 특정 시기에 따른 심리적, 신체적 요인을 고려해야만 한다. 그렇기에 여학생들의 신체활동 환경을 둘러싼 요인을 종합적으로 구조화하여 모델로 구성하는 작업이 현 시점에서 가장 필요한 일일 수밖에 없다. 그래야 홍보에서부터 수업 설계, 환경적 분위기 조성을 위한 여러 정책 개발도 가능해지기 때문이다.

아쉽게도 이러한 요인을 종합하거나 구조화하는 연구가 국내에서는 지금껏 상당히 미흡했다. 중고등학교 여학생을 대상으로 신체활동의 촉진 및 저해요인을 인지/심리적, 물리/환경적, 신체적, 사회/문화적 차원으로 단순 분류한 연구(Lee, 2010) 이외의 나머지 연구는 대부분이 요인 나열이나 이론적 검토, 혹은 재미거리와 걱정거리를 탐색하는 수준에 머물렀기 때문이다. 즉, 관련 요인의 산발적 나열에 그쳤으며 요인 간 관계와 메커니즘을 거시적으로 접근한 연구가 거의 없는 실정이다. 때문에 관련된 정책을 설정하는데 있어서도 단순히 요인 중심의 접근(선호종목 제공 등)이 주로 적용될 수밖에 없었다. 한 마디로, 여학생의 신체활동을 둘러싼 ‘맥락성’을 고려할만한 참고자료가 부족한 것이다.

향후 인구구조 변화나 비만 인구 증가에 따라 더욱 지대한 정책적 관심을 받게 될 신체활동의 문제를 고려한다면, 나아가 그 관심사에서 소외된 여성의 현 상황을 생각한다면, 관련 정책과 프로그램의 개발에서부터 캠페인 기획을 위해 여학생들의 신체활동 참가를 저해하거나 촉진하는 요인 간의 관계를 종합적으로 이해하려는 노력은 간과할 수 없는 중요성을 지닌다.

이를 위한 선행 작업으로서 우리보다 앞서 여학생의 신체활동 증진을 고민한 해외사례를 검토해볼 필요가 있다(Carlson, 1995; Knowles, Niven & Fawkner, 2011; Standiford, 2013; Whitehead & Biddle; 2008). 오래 전부터 여학생의 신체활동 불참에 따른 개인의 건강과 삶의 질 저하, 이에 수반되는 사회적 비용 문제를 입증하며 여학생의 신체활동을 증진코자 지속적인 노력을 경주해 왔던 이들 결과물이 우리에게 줄 시사점이 매우 크기 때문이다. 즉, 신체활동을 향한 여학생의 인식에서부터 참여를 촉진하고 저해하는 구체적 맥락의 고민 지점을 파악할 수 있도록 해주기 때문이다.

나아가 이와 같은 학술적 접근이 실제로 정책적으로 어떻게 구현될 수 있는가를 바라볼 수 있도록 해줄 수도 있다. 실제로 몇몇 해외 국가의 경우 여성을 위한 다양한 프로그램을 실시하는데, 80여개의 스포츠 종목 참가를 지원하면서 여학생들의 신체활동 참가를 돕는 영국의 ‘This Girls Can’ 캠페인이나, 학교와 지역사회 간 여학생 신체활동 파트너십을 구성한 스코틀랜드의 ‘Fit for Girls’ 프로그램, 여학생들의 신체활동과 연관된 심리사회적 요인들을 분석하고 지방 부처, 코치, 가족들을 위한 가이드라인 및 권고 사항을 제시한 캐나다의 사례 등은 거시적으로 여학생 신체활동과 관련된 요인을 다양한 층위에서 분석하여 얻은 연구물과 조우한 결과이다. 여학생 신체활동 관련 해외연구물을 심층적으로 분석해봐야 할 이유의 또 다른 축이기도 하다.

이에 이 연구는 여학생들의 신체활동을 촉진시키고 저해하는 요인의 사회문화적 측면이 어떤 관계로 구성될 수 있는가를 가설적으로 모형화하고자 한다. 이 목적을 달성하고자 첫째, 여학생들의 신체활동 참가와 관련되어 해외에서 이루어진 선행연구의 결과는 어떠한지를 밝혀내고, 둘째, 그 요인들이 종합적으로 어떤 범주를 형성하여 개념화될 수 있는가를 분석하며, 마지막으로 개념범주들 간의 인과적 관계가 환경적, 관계적, 개인적 차원에서 어떻게 구조화할 수 있는가를 가설적으로 모형화하려는 세 가지 연구질문이 설정되었다.

이와 같은 작업은 향후 우리들에게 의미 있는 통찰을 제시해줄 수 있다. 즉, 여성이라는 ‘공통성’과 환경적 맥락이라는 ‘상이함’ 속에서 먼저 고민된 해외 연구 결과는 특정 대상의 현 조건을 긍정적인 방향으로 발전시키는데 필요한 여러 중요 정보를 제공해줄 수 있기 때문이다. 또한 이러한 작업은 향후 필수적으로 이루어질 국내 여학생들의 저조한 신체활동 참여를 개선시킬 요인 탐색 작업의 이론적 기반이 되며, 관련 문제의 개선점과 정책 마련에도 적지 않은 길잡이 역할을 해줄 것이다. 나아가 학교 현장의 실천 과정에 방향을 제시해줄 수 있을 뿐 아니라 구체적 변화도 모색하고, 여학생 신체활동과 관련한 세부적이고 구체적 지침을 세우는 데에도 기초 자료로서 도움을 줄 수 있을 것이다.

연구방법

해외에서 이루어진 여학생 신체활동 참가 연구를 종합적으로 분석함으로써 가설적 모형을 구성하기 위해 본 연구에서 설정한 연구방법은 다음과 같다.

분석대상 및 수집절차

이 연구의 분석대상은 여학생 신체활동 참여 및 저해 요인과 관련하여 해외에서 이루어진 총 26편의 연구물이다. 이들은 구글 학술검색과 EBSCO에서 ‘신체활동(physical activity, physical education, exercise, sport)’, ‘여학생(adolescent girl, female)’, ‘참가(participation)’, ‘질적연구법(qualitative methods, methodology)’ 검색어를 교차 입력하며 수집되었다. 2005년부터 2016년까지의 기간을 대상으로, 영어로 게재된 연구물을 수집하였다. 연구물의 수집 시작 년도를 2005년으로 설정한 이유는 2005년이 미국의 Title IX 시행 30년이 되던 해로 미국 교육 당국이 Title IX 시행과 관련해 그 간의 업적을 평가, 가이드라인을 제공하였고, UN 역시 2005년을 국제 스포츠 교육의 해(International Year of Sport and Physical Education 2005)로 지정하여 여학생들의 스포츠 참여를 증진시키기 위해 노력한 해이기 때문이다(UN, 2005; U.S. Department of Eucation, 2005; The National Coalition for Women and Girls in Education, 2012). 그 이후 약 10년간의 주요 연구물을 통해 여학생들의 참여 촉진 또는 저해 요인을 전반적으로 파악하고자 2016년까지로 수집 기간을 설정하였다. 그 결과 총 40개가 검색되었다. 이들을 대상으로 연구자는 1) 제목 수준에서 여학생 신체활동 및 스포츠 참가 촉진 및 저해 요인이 명시된 연구물 2) 초록에서 여학생 신체활동 참여 촉진 및 저해 요인이 연구결과로 명시된 연구물, 3) 여학생의 특징 분석 및 신체활동 참가 요인을 밝혀낸 연구물이라는 세 가지 기준을 가지고 먼저 분류를 실시하였다.

사전 분류를 실시하면서 본 연구의 목적과 부합하지 않는 주제의 연구물이 제외되었다. 예를 들어, 남녀학생 모두를 연구대상으로 삼은 연구 중 여학생의 참여 요인을 파악할 수 있는 연구 결과는 분석 대상으로 삼았지만 남학생과 여학생의 참여 특성이 명확히 구분되지 않은 연구는 제외하는 식이었다(Bauer, Yang & Austin, 2004; Hohepa, Schofield & Kolt, 2006). 연구방법 측면에서 양적 연구방법과 질적 연구방법을 혼합하여 진행한 연구 중 여학생의 면담 내용이 명확히 구분되고 신체활동 참가 요인 및 이유가 드러난 부분은 분석 대상으로 삼았으나 그렇지 않은 경우에는 제외되었다.

또한 연구물을 반복해서 읽으면서 연구 결과 및 결론에서 제시하고 있는 내용과 본 연구의 목적이 부합되지 않는 연구도 제외되었다. 예를 들어, 댄스 프로그램 효과와 교사 전략 연구(Watson, Adams, Azevedo & Haighton, 2006)나, 민족이나 인종에 따른 신체활동 인식 연구(Grieser, Vu, Bedimo-Rung, Neumark-Sztainer, Moody, Young & Moe, 2006), 나아가 과체중 청소년을 대상으로 한 연구(Stankov, Olds & Cargo, 2012)와 같이, 특정 프로그램과 대상을 통해 신체활동 참여 요인 및 효과를 밝힌 연구 역시 본 연구의 목적 달성과 관련이 없기에 제외시켰다. 총 14편이 제외시킬 연구물로 선정되었고, 이를 제외한 후 최종적으로 26편의 논문이 분석대상으로 선정되었다.

분석절차

수집된 자료는 몇 가지 범주를 중심으로 분석되었다. 분석범주는 연구의 출판년도, 목적, 연구대상, 분석방법, 주요결과 중심으로 설정되었고, 연구의 주요결과로 제시된 내용 중 여학생의 신체활동 참가와 관련된 여러 요인은 신체활동 참가 촉진요인(△)과 저해요인(▼), 요인의 하위 특성에 따라 촉진 또는 저해의 가능성을 모두 지닌 요인(◎)으로 표시 및 분류되었다. 촉진요인이란 각 연구에서 여학생들의 신체활동 참가를 활발하게 만드는 개인적, 관계적, 환경적 변수였고, 반대로 저해요인은 그러한 신체활동의 장벽(barriers)으로 기능하는 변수로 각각 정의된 후 분석 과정에서 정리되었다.

이와 같은 분석범주에 따라 개별 연구자들은 분석대상인 26편의 연구물을 반복적으로 독해하고 분석틀에 맞춰 어떤 요인이 여학생을 신체활동에 참가하게 하거나 저해하는지 정리하였다. 이 과정에서 분석 자료로 삼은 원자료의 분류체계와 그 의미를 최대한 유지하고자 했다. 이를 위해 연구자들은 각자 분석한 자료를 가지고 동료 검토(peer review)를 실시했다. 먼저 각 연구자들이 개별적으로 요인들의 내용을 검토하여 각각의 개념을 구성한 후, 함께 모여 그 내용의 타당성을 논의하였다. 이 과정에서 신체활동 참가와 관련한 선행연구 및 이론이 삼각검증의 도구로 활용되었고(e.g., Spence & Lee, 2003; Vilhjalmsson & Thorlindsson, 1998), 이러한 과정을 거치면서 연구자 간 합의가 이루어질 때까지 논의를 하였고, 최종 개념화에 도달하였다.

이렇게 분류된 촉진요인과 저해요인은 앞서 설정한 정리 범주에 따라 표로 재정리되었고, 이들 각 요인은 귀납적으로 범주화된 후 인과관계를 형성하기 위한 작업으로 이어졌다. 이들 범주는 개인적, 관계적, 환경적 차원으로 분류된 후 신체활동 관련 이론 및 연구가 참고되어 범주 간 인과관계성이 설정되었으며, 최종적으로 가설적 모형으로 구성되었다.

연구결과 및 논의

<Table 1>에 정리된 연구결과는 어떠한 요인에 의해 여학생들의 신체활동이 촉진되고 저해될 수 있는지를 잘 보여준다. 여기에서 중요한 점은 각 연구가 밝혀냈던 요인들이 어떻게 범주화되어 신체활동과 관련한 경향성으로 나타나는가이다. 신체활동 촉진과 저해요인이 주요 범주 중심으로 설명되어야 할 이유다. 때문에 본 연구는 <Table 1>에 제시된 각 요인을 범주화하여 신체활동 촉진요인 모형(SPORTS)과 저해요인 모형(INCAPABLE)으로 재배치한 후 이들의 관계를 정리하였다.

여학생 신체활동 촉진요인으로서의 SPORTS

여학생의 신체활동을 촉진하는 사례들은 크게 여섯 가지로 요약된다. 먼저 가장 중요하게 언급되었던 ‘자기인정(지)(Self-Recognition)’을 시작으로, 신체활동과 관련된 주변 환경 조건으로서의 ‘물리적 환경(Physical Environment)’, 종목이나 시간의 선택을 가능케 하는 ‘기회(Opportunities)’, 중요타자와의 지속적 상호작용을 전제하는 ‘관계형성(Relationship)’, 신체활동을 스스로 다룰 수 있는 조건으로서의 ‘적합성(Treatment)’, 마지막으로 부모나 교사, 친구에게 직간접적으로 받는 ‘사회적 지지(Social Supports)’가 그것이다.

촉진요인1: 자기인정(지)(Self-Recognition)

첫 번째로 범주화한 신체활동 촉진요인은 ‘자기인정(지)’이었다. 이는 ‘여학생들이 자신의 신체적, 심리적 측면을 긍정적으로 평가할수록 신체활동에 적극적으로 참여한다’는 명제로 이해되는 요인이다. 즉, 많은 선행연구에서 밝혔듯, 이 ‘자기인정’은 자신의 운동능력이 뛰어나거나 신체 이미지가 좋다고 인정/인지할 때(Biddle, Whitehead, O’Donovan, & Nevill, 2005; Hills, 2007; Coleman, Cox, & Roker, 2007), 혹은 자신의 가치가 높다고 인정할 때(Yungblut, Schinke, & McGannon, 2012), 신체활동으로 인해 자신이 즐거움을 느낄 수 있음을 인지할 때(Standiford, 2013) 여학생들의 신체활동 참가가 촉진된다. 이 결과는 교육현장에서 여학생들의 ‘유능감’을 높여줄 수 있도록 ‘신체활동에서의 성공 자주 경험하기’ 차원의 교수법에서부터, 사회적으로 ‘여성도 운동을 할 수 있다’는 메시지를 전파할 분위기 형성에 이르기까지, 어떠한 노력이 필요한지를 잘 말해준다. 실제로 영국의 경우, 여성의 활동적인 삶을 위하여 스포츠 잉글랜드의 지원 하에 ‘This Girl Can’이라는 캠페인을 벌이며 큰 호응을 얻고 있는데, 본 연구의 ‘자기인정’ 요소의 중요성을 사회적 차원에서부터 형성해나가려는 좋은 사례로 볼 수 있다.

촉진요인2: 물리적 환경(Physical Environment)

두 번째 촉진요인은 물리적 환경이다. 이 요인은 여학생들이 신체활동을 편하게 즐길 수 있는 환경 조건이 잘 갖추어졌을 때 참가가 증진됨을 말해준다. 스포츠나 운동과 같은 신체활동은 기본적으로 시설이나 용구와 같은물적 기반이 제대로 갖추어지지 않고서 참가가 촉진될수는 없기에, 이 범주는 어떤 측면에선 매우 자연스러운 결과일 수 있지만, 여기엔 시설과 용구만이 포함되는 것은 아니다. 예를 들어, ‘공평한 경쟁조건이 마련되었을 때(Azzarito, Solmon, & Harrison, 2006)’라거나, ‘활동하기 편안한(cozy) 분위기가 형성되었을 때(Vu, Murrie, Gonzalez, & Jobe, 2006)’, 나아가 ‘학교에서 남녀가 분반되었을 때(Casey, Eime, Payne, & Harvey, 2009)’ 신체활동에 적극 참가하겠다는 의견이 발견되었던 것이다. 이러한 반응은 이 연구의 후반에 나오는 ‘저해요인’ 중 여학생들을 불편하게 만드는 조건과도 밀접한 관련을 맺는다. 기본적으로 신체활동 자체가 자연 환경이 아닌, 구성된 환경(built environment)에서 대부분 이루어지기에, 이처럼 물리적 환경을 적절하게 조성하는 작업은 비단 이 연구 뿐 아니라 향후 다각적인 방향에서 심도 있게 논의될 필요가 있다.

촉진요인3: 기회(Opportunities)

세 번째 촉진요인은 ‘기회’로 종합되었다. 이 요인은 여학생들에게 운동 종목이나 운동을 할 시간을 포함하여 일종의 ‘선택 기회’를 제공했을 때 신체활동 참가가 촉진될 수 있다는 명제로 이해된다. 다시 말해, 선택지를 최대한 많이 제공해줌으로써 여학생들의 ‘주도적 선택권’을 높여주는 것이 신체활동 촉진으로 이어질 수 있다는 뜻이다. ‘신체활동의 선택기회(Biddle, et al., 2005; Gillison, Sebire, & Standage, 2012)’가 제공되거나 그러한 기회가 ‘나의 선호도에 맞는 신체활동과 연관(Gruno & Gibbons, 2016)’ 될 때, 나아가 ‘운동할 시간적 기회가 제공(Knowles, et al., 2011)’되거나, 구체적으로 ‘어떤 신체활동을 할지 스스로 결정할 기회가 제공될 때(Loman, 2008)’ 여학생들의 신체활동은 촉진될 수 있다. 이러한 결과는 실기 교과목을 교사들이 미리 정한 후 여학생들에게 참여를 강요하는 우리나라 대부분의 교육현장에 시사하는 바가 크다.

촉진요인4: 관계 형성(Relationship)

여학생들의 신체활동을 촉진시킬 네 번째 요인은 ‘관계 형성’으로 범주화하였다. 이 범주는 운동이나 체육수업, 스포츠 활동을 할 때 관련되는 중요타자와의 긍정적 관계가 형성되면 여학생의 신체활동 참가가 촉진된다는 명제로 이해된다. 즉, 신체활동을 하면서 얻을 수 있는 혜택 차원인 것이다. 특히 여학생들이 주로 언급했던 혜택은 신체활동이 ‘친구와의 우정을 형성할 기회로 인정될 때(Coleman, et al., 2007; O’Donovan & Kirk, 2008; Shannon, 2016)’ 참가가 촉진될 수 있다고 언급한 지점이다. 여성 특유의 관계 지향성을 엿볼 수 있는 결과라 하겠다. 더불어 ‘긍정적인 사회관계 및 사회자본 형성의 기회(Hills, 2007; Whitehead, & Biddle, 2008)’나 ‘성인(부모 및 교사)과의 관계를 원만하게 하는데 도움(Gillison, et al., 2012)’이 될 때도 신체활동 촉진요인으로 작용하였다. 이와 같은 결과는 특히 여성을 위한 신체활동 프로그램이 어떤 방식으로 구성되어야 하는지를 잘 보여준다고 하겠다. 즉, 개인적으로 즐길 수 있는 프로그램만이 아닌, 다른 학생들과 함께 교류하는 ‘협동’과 운동기술로 겨루는 ‘경쟁’이 포함된 일종의 ‘협쟁(coopetition)’ 형태의 프로그램이 적합할 수 있다는 연구결과를 보여준다는 것이다.

촉진요인5: 적합성(Treatment)

‘적합성’으로 명명된 다섯 번째 요인 또한 앞서 언급되었던 여학생들의 행위성(주체성)과 관련되며, 여학생들에게 자신이 다룰 수 있는 활동이나 시간적 조건을 제공해주어야 함을 말해준다. 즉, 여학생들은 자신들이 신체활동하기 적합한 상황, 예를 들어 참가 장소 및 시간이 적절하여 자신이 통제할 수 있는 상황이 주어질 때 참가가 촉진될 수 있다는 뜻이다. 대표적으로, ‘운동 종목이 공평한 경쟁으로 이루어질 수 있을 때(Azzarito, et al., 2006)’나 ‘시간을 스스로 활용할 수 있는 상황이 주어졌을 때(Eime, et al., 2008)’, 나아가 ‘흥미를 느껴 참가할만한 활동이 주어졌을 때(Standiford, 2013)’, ‘운동하는 장소가 접근 및 이용 가능할 때(Niven, et al., 2014)’, 신체활동 참가 촉진이 이루어질 수 있다는 것이다. 결국 여학생들의 신체활동 참가를 이끌어내기 위해서는 운동 종목의 다양성에서부터 활동 형태(개인운동 혹은 팀 운동)가 감당할만한 것으로 조건화되어야 함을 연구결과는 말해준다.

촉진요인6: 사회적 지지(Social Supports)

여학생의 신체활동 촉진요인 마지막은 ‘사회적 지지’다. 이 요인은 부모, 교사, 친구와 같은 중요타자가 자신의 신체활동에 대하여 긍정적인 지지를 보내줄 때 여학생들의 신체활동 참가가 이루어진다고 말해준다. 이 명제는 예를 들어, ‘부모의 지지나 동료의 관여와 지지, 가족들이 지지해줄 때(Biddle, et al, 2005)’, 즉 ‘중요타자의 지지가 있을 때(Coleman, et al., 2007)’나 ‘자신의 참가에 대하여 긍정적으로 격려해 줄 때(Vu, et al., 2006)’와 같은 사례로 구성된 범주인 것이다. 특히 여학생들은 부모가 신체활동에 대해 감정적으로 지원해줄 때 더 큰 영향을 받았다(Wright, Wilson, Griffin, & Evans, 2010; Knowles, et al., 2011; Gillison, et al., 2012). 결국 이 역시 첫 번째 촉진요인인 ‘자기 인정’과 함께 여학생도 신체활동에 어울릴 수 있음을 일깨워주는데 중요한 역할을 하는 것으로 볼 수 있다.

여학생 신체활동 저해요인으로서의 INCAPABLE

여학생들의 신체활동 저해요인은 총 아홉 개로 범주화하였다. 이 범주는 ‘무엇인가를 하지 못한다’는 뜻의 ‘INCAPABLE’로 정리되었는데, 구체적으로 살펴보면, ‘내면화된 시선(Internalized Gazes)’, ‘부정적 피드백(Negative Feedback)’, ‘경쟁성(Competitiveness)’, ‘대체활동 우세성(Alternativeness)’, ‘인지된 위험성(Perceived Danger)’, ‘외모 인식(Appearance)’, ‘신체활동에 대한 불쾌한 감정(Bad Feeling)’, ‘기회 부족(Lack of Opportunities)’, ‘여성적 규범(Effeminate Norms)’으로 세분화되어 나타났다. 각 범주에 대한 세부적인 내용은 다음과 같다.

저해요인1: 내면화된 시선(Internalized Gazes)

첫 번째 저해요인은 ‘내면화된 시선’으로 명명되었다. 여기에는 여학생들이 자신들의 신체활동과 관련하여 다른 사람들의 시선을 의식하며 그 시선의 기준에 맞춰 행동을 선택한다고 응답한 내용이 포함되었다. 즉, 타자의 시선을 내면화한다는 뜻이다(cf., Evans, 2006). 이와 같은 시선의 내면화 문제가 많은 연구에서 보고되었는데, 이는 ‘타인의 시선을 체화할수록 여학생들은 신체활동에 참가하지 않으려 한다’는 명제로 연결될 수 있다. 연구의 몇몇 사례를 살펴보면, ‘남학생 앞에서 우습게 보일까봐 신경 쓰이고(Azzarito, et al., 2006)’, ‘남학생들의 반응이 두려우며(Standiford, 2013)’, ‘복장이나 몸에 대한 타인의 시선(Slater & Tiggemann, 2010; Spencer, Rehman, & Kirk, 2015)’이 신경 쓰여 ‘계속 나 자신의 신체 이미지를 생각(van Daalen, 2005)’하며 ‘타인의 평가가 어떠할지를 자꾸 염려(Yungblut, et al., 2012)’하게 된다는 것이다. 결국, 이와 같은 주요 사례는 여학생들이 타인의 시선에 민감해질수록 활발한 신체활동 참가가 저조해질 것이고, 내면화된 시선의 문제를 어떻게 변화시킬지를 고민해야 함을 말해준다.

저해요인2: 부정적 피드백(Negative Feedback)

신체활동 참가 저해요인의 두 번째 범주는 중요타자에게 받는 ‘부정적 피드백’으로 나타났다. 이 범주는 부모나 교사, 코치, 친구 등과 같은 중요타자에게 긍정적이지 못한 피드백을 받게 되면 여학생들이 신체활동에 참가하지 않으려 한다는 명제를 지닌다. 즉, 신체활동 참가 촉진 요인 중 ‘사회적 지지’와 정 반대의 내용인 것이다. 부정적 피드백으로 제시되었던 사례로는, ‘교사의 젠더와 인종적 편견으로 인한 절망(van Daalen, 2005)’에서부터, ‘남자체육교사의 부정적 피드백(Casey, et al., 2009; Vu, et al., 2006)’, ‘부모의 부정적 지지(Knowles, et al., 2011; Slater & Tiggemann, 2010)’나 ‘운동보다는 숙제 및 공부를 더 독려하는 경향(Dwyer, Allison, Goldenberg, & Fein, 2006)’ 및 ‘주변에서 (신체활동 할 때) 바보처럼 보인다고 받는 평가(Coleman, et al., 2007)’ 등이 거론되었다. 특히 이와 같은 주변의 부정적 피드백은 어린 나이대의 여학생들이 신체활동을 대하는 ‘태도’에 매우 큰 영향을 미치기에 중요한 문제다. 특정 행동을 선택하는데 있어 자신의 결정에 주변(물적, 인적) 환경의 ‘평가’가 먼저 고려되기 때문이다. 또한 여학생의 신체활동을 향한 주변 평가가 부정적으로 형성되어 있는 상황에 반(反)함으로써 얻을 수 있는 이점과 감수해야만 할 ‘대가’를 계산하는 것 역시 최종 선택에 중대한 영향을 미치기 때문이기도 하다(Epstein, 1998; Lenskyj, 1995). 앞선 내면화된 시선과 더불어 여학생들 스스로의 주도적 선택 역량을 저해한다는 차원에서 중요타자들의 부정적 피드백은 여학생 신체활동 참가에 매우 민감한 문제가 된다.

저해요인3: 경쟁성(Competitiveness)

여학생들의 신체활동 저해요인은 또한 ‘경쟁성’이란 범주로 재구성되었다. 세 번째 범주로 구성된 이 ‘경쟁 요인’은, 신체활동과 관련하여 만들어진 경쟁 환경이 여학생들에게 부담으로 작용할 때 신체활동 참가는 연기될 수 있음을 그 명제로 삼는다. 구체적으로 여학생들은 ‘신체활동에 동반되는 지나친 경쟁(Casey, et al., 2009; Gruno & Gibbons, 2016)’과 ‘남학생과의 경쟁에 대한 거부감(Knowles, et al., 2011)’을 주된 저해요인으로 거론했고, 나아가 그러한 경쟁이 주는 ‘승리에 대한 압박감이나 스트레스(Dwyer, et al., 2006)’와 ‘팀 스포츠에서 실수할까하는 두려움(Standiford, 2013)’을 신체활동으로의 참가를 막는 요인으로 제시하였다. 이처럼 경쟁요인이 여학생들의 신체활동 참가를 저해하는 이유는 여성이 지니는 스포츠 참가의 사회적 가치 때문이기도 하다. “여성은 재미, 우정, 연결과 같은 스포츠 참가의 사회적 측면에 가치를 부여한다(Lenskyj, 1995, p. 9).” 나아가 신체활동(체육수업을 포함한)에서의 지나친 경쟁은 기본적으로 ‘평가’를 수반하는데 이는 앞서 언급되었던 ‘부정적 피드백’과도 연결되는 지점이기도 하다(van Daalen, 2005).

저해요인4: 대체활동(Alternativeness)

여학생들은 스포츠나 운동 이외에 숙제나 다른 여가 활동 때문에 신체활동 참가가 저해된다고 보고하기도 하였다. 이는 ‘대체활동이 지니는 우세성’으로 명명될 수 있는 범주로서, 다른 활동(숙제, 친구와의 수다, 쇼핑 등)의 중요성이 더 높게 인지될 때 여학생들은 신체활동에 참가하지 않게 된다는 명제를 포함한다. 여기에는 ‘숙제가 많고 주말에는 부모님과 시간을 보내며 아르바이트 및 가사일(Dwyer, et al., 2006)’이나 ‘과제로 인한 여유 부족 및 TV 시청이나 인터넷과 같은 테크놀로지 활동(Biddle, et al., 2005)’, 10대가 되면서 운동과 같은 활동에서 다른 활동, 예를 들어 남자친구 만나기나 시내에 나가 놀기 등, ‘우선순위의 변화(Whitehead & Biddle, 2008)’, 여기에 덧붙여 ‘다른 취미활동이나 사회적 활동 선호(Wright, et al., 2010)’ 및 ‘중학교에 올라와 대안적 활동에 관심(Knowles, et al., 2011)’을 갖는 이유 등이 포함되었다.

저해요인5: 위험 인지(Perceived Danger)

신체활동에 언제나 수반되는 ‘위험성’ 역시 여학생들이 인식하는 신체활동 참가 저해요인 중 하나였다. 다섯 번째 범주로 나타난 이 요인은 ‘신체활동이 이루어지는 환경이나 활동 자체가 위험할 것 같다고 인식되면, 여학생들은 신체활동에 참가하려 들지 않을 것’이라는 명제로 구성된다. ‘다칠지 모른다는 생각(Dwyer, et al., 2006)’이나 ‘부상 걱정(Slater & Tiggemann, 2010)’이 먼저 들 때, 나아가 신체활동이 이루어지는 공간과 관련한 ‘안전 우려(Standiford, 2013)’가 다섯 번째 저해 요인인 ‘인지된 위험성’에 포함된 내용이었다. 학교 운동장에서의 젠더 재생산을 다룬 국내 연구에서도 이와 같은 내용이 확인된 바 있는데, 남학생들은 위험을 ‘극복해야 할 대상’으로 여기는 반면, 여학생들은 신체활동의 위험성을 ‘회피 대상’으로 간주하는 경향이 강했다고 보고된 바 있다(Nam & Lee, 2006).

저해요인6: 외모 인식(Appearance)

여학생들의 신체활동 참가를 저해하는 여섯 번째 범주는 ‘외모 인식’으로 명명되었다. 이 범주에 따르면, 외모에 대한 자기 자신 혹은 타인의 평가가 지나칠수록 여학생들은 신체활동으로의 참가에 소극적이 될 수밖에 없음을 보여준다. 신체활동 자체가 외모를 어느 정도 헝클어트릴 수밖에 없음에도, 그것이 문제가 된다면 여학생들은 신체활동으로의 참가를 선택하지 않기 때문이다. 실제로 많은 선행연구에서는 이와 유사한 반응을 결과로 제시하였다. 예를 들어, 다른 무엇보다도 ‘외모와 복장(너무 타이트하다고 느낌)에 신경을 쓰게 되거나(Whitehead & Biddle, 2008)’, 신체활동을 함으로서 ‘헝클어진 머리나 화장이 지워지는 것에 우려감(Standiford, 2013)’을 지니는 경우, 나아가 ‘다른 아이들에게 내 외모가 어떻게 평가될지 두렵거나(O’ Donovan, & Kirk, 2008), 다른 사람의 인식이 우려스러운(Spencer, et al., 2015)’ 경우, 여학생들은 신체활동에 참가하지 않았다. 결국, 자신의 신체활동에 대한 평가 기준이 자신인지, 타자인지에 따라 참가여부가 결정된다는 것이다. 이는 여학생들의 ‘자기 대상화(self-objectification)’가 적극적인 신체활동 참가에 걸림돌이 될 수 있다는 이론을 실증적으로 뒷받침해준다.

저해요인7: 불쾌한 감정(Bad Feelings)

일곱 번째로 드러난 신체활동 저해요인은 신체활동에 수반되는 ‘불쾌한 감정’으로 명명되었다. 이 요인범주는 신체활동 자체적으로나, 혹은 그것으로 인해 수반되는 불쾌한 느낌과 감정이 클수록, 여학생들의 신체활동 참가 수준은 낮아질 수 있음을 말해준다. 이와 관련하여 가장 대표적으로 거론되는 반응은 신체활동으로 인해 ‘땀이 나는 것에 대한 거부감이나 그로 인한 스포츠 참가가 꺼려지는(Coleman, et al., 2007)’ 상황과 이를 해결 할 ‘샤워시설의 부재로 인해 땀 등의 불쾌감이 해소되지 못하는 상황(Yungblut, et al., 2012)’이 제시되었다. 더 나아가 최근 국내에서도 문제가 된 ‘성차별과 성희롱’에서부터 신체활동 맥락이 제공하는 ‘두려움, 끔찍함, 당황스러움, 불안감, 압박감 등의 불쾌한 감정(van Daalen, 2005)’ 등도 이 일곱 번째 범주를 형성하는 대표적인 사례였다. 즉, 신체활동에 따라오는 경쟁성이나 승리에 대한 지나친 압박이 여학생들로 하여금 참가를 꺼리게 만든다는 내용이었다. 이는 앞서 언급되었던 ‘지나친 경쟁’ 요인과 맥을 같이 하면서, 여학생들을 위한 신체활동 프로그램이 어떻게 설계되어야 하는가를 시사해주고 있는 내용이라 하겠다.

저해요인8: 기회 부족(Lack of Opportunities)

신체활동과 연계된 ‘기회’가 전반적으로 부족하다는 내용이 여학생들의 신체활동 참가를 저해하는 여덟 번째 요인으로 범주화되었다. 이 기회 요인은 적합한 프로그램에 참여할 수 있는 여건, 시간, 시설로의 접근성 등을 주로 포함하면서, 신체활동에 참가할 수 있는 기회가 적을수록 여학생들은 다른 활동으로의 참가를 선택하게 된다는 명제를 지닌다. 관련하여 선행연구에서 빈번하게 언급된 내용으로는 우선 ‘배제에 따른 기회 박탈’이 논의될 수 있다. 즉, ‘경쟁에 따른 참가 배제로 기회가 박탈(Casey, et al, 2009)’되거나 ‘남학생과 함께 할 때 배제됨으로써 기회가 없어지는(Slater & Tiggemann, 2010)’ 상황이 만들어진다는 것이다. 나아가 ‘시설 이용의 기회 제한 및 접근성이 떨어지는(Dwyer, et al., 2006)’ 문제와 ‘시간 부족(Eime, et al., 2008)’, 여기에 덧붙여, 체육수업에서 전통적인 스포츠만 진행함으로써 여학생이 할 수 있는 스포츠 종목의 선택을 제한하는(Azzarito, et al., 2006; Slater & Tiggemann, 2010) 문제 등이 포함되었다.

저해요인9: 여성적 규범(Effeminate Norms)

스포츠가 여성적이지 않다는 사회적 인식 역시 여학생들의 신체활동 저해요인 중 하나를 차지하였다. 즉, ‘여성적 규범’으로 명명된 마지막 저해요인과 관련, 선행연구는 여성다움의 기준이 강하게 발현되는 환경적 조건일수록, 여학생들의 신체활동 참가는 저해된다고 말해주고 있었다. ‘이 신체활동으로 인해 나의 여성성이 훼손되지는 않을까’란 걱정이 드는 순간, 여학생들은 신체활동으로의 참가를 철회한다는 뜻이다. 즉, ‘신체활동을 하는 것에 대하여 남정네(tomboy) 같다고 인식(Vu, et al, 2006)’하고, 이에 따라 공격적인 신체활동이 불가능하다고 생각하거나 ‘여학생은 축구를 할 수 없다는 암묵적 기준(Hills, 2006)’을 따르며, ‘활발한 신체활동을 하는 것은 여성으로서 쿨하지 못한(uncool) 선택(Slater & Tiggemann, 2010)’으로 수용되는 경우다. 결국, 이러한 인식과 반응은 사회적으로 형성된 ‘여성성에 대한 편견(Dwyer, et al., 2006)’과 더불어 ‘사회에서 기대되는 여성적인 행동규범(Standiford, 2013)’ 때문으로 해석된다. 그러한 여성적 규범을 어린 나이 때부터(실제로 이 연구에서 인용된 26편의 연구 대부분은 초중고등학생을 대상) 신체활동 맥락에서 체화한 여학생들은, 향후 전 생애에 걸쳐 신체활동 참가 지향적인 삶을 살지 못하게 될 가능성이 높을 수밖에 없게 된다.

여학생 신체활동 촉진 및 저해요인의 가설적 모형

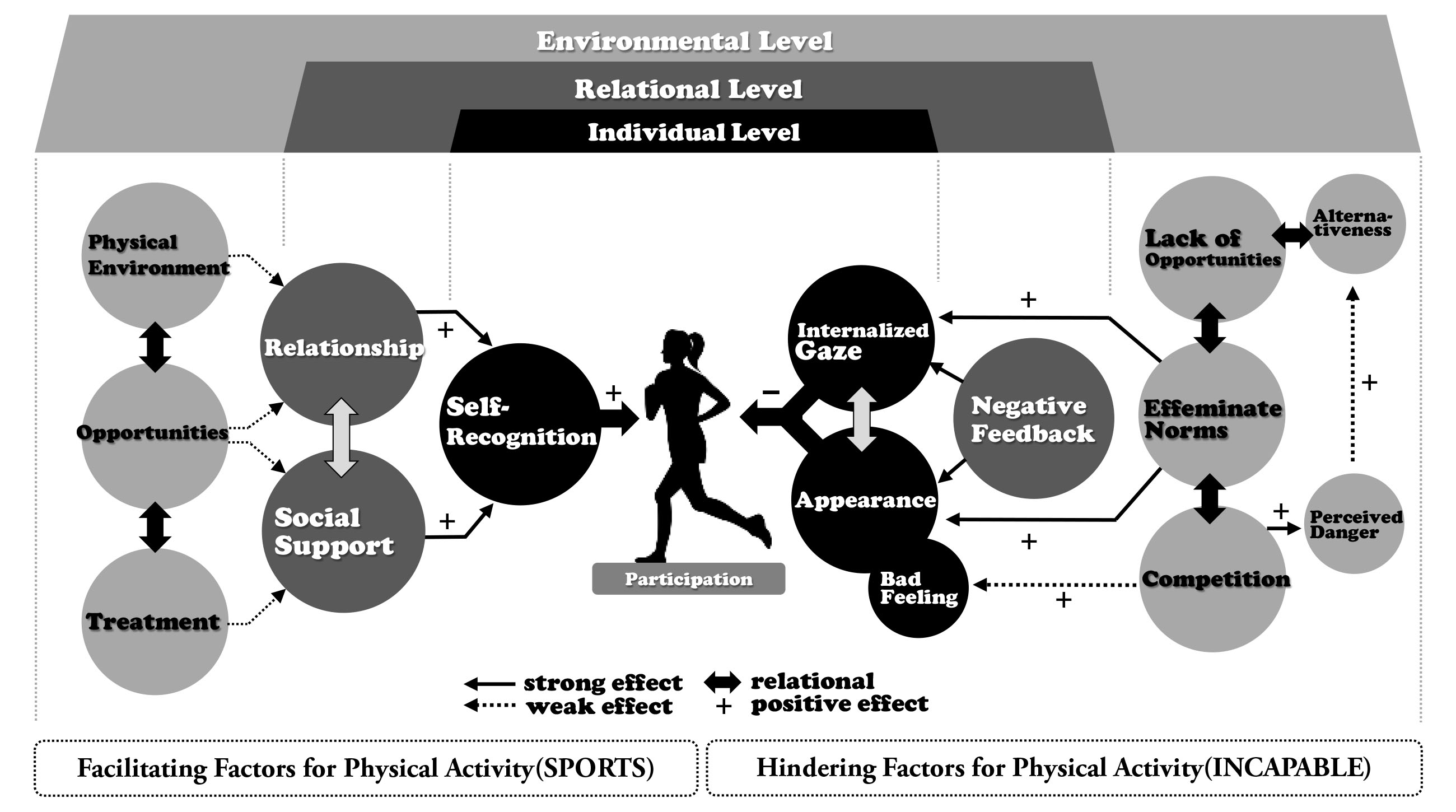

지금까지 여학생 신체활동과 관련한 경향성을 촉진요인과 저해요인으로 범주화하여 설명하였다. 이러한 요인의 범주화에서 한 발 더 나아가, 본 연구는 이들 각 요인범주가 나름의 관계를 맺고 있으리라는 가정 하에 총 15개의 요인범주 간 인과관계를 설정하였고, 그 결과 다음의 <Fig. 2>와 같은 가설적 모형을 구성하였다. 이 모형은 여학생들의 신체활동 참가 촉진과 저해요인이 환경적 차원과 관계적 차원, 그리고 개인적 차원으로 구조화되어 상호 간 인과관계를 형성하고 있음을 보여준다.

A hypothetical model of facilitating and hindering factors for physical activity of female adolescent

먼저 신체활동 참가촉진과 관련한 요인범주 관계모형에 따르면, 여학생들의 신체활동 참가를 촉진하기 위해서는 무엇보다 학생 개개인이 자신의 심신과 관련한 요소를 긍정적으로 인정하게 만드는 일이 중요함을 알 수 있다(자기인정). 즉, 여학생들은 ‘능력이 좋아’, ‘운동을 잘해’, ‘운동하는 것이 나에게 어울려’ 등과 같이 신체활동과 관련된 자신의 내적요소에 대해 긍정적 인식을 가질 때 비로소 신체활동 참가로 연결된다는 뜻이다.

모형에 따르면, 이러한 자기인정은 무엇보다도 ‘관계적 차원’에 의해 정적인 영향을 받을 수 있다. 다시 말해, 친구나 다른 중요타자와의 관계 형성과 그들에게서 받는 사회적 지지로 인해 여학생들이 신체활동과 자신에 대한 인식 사이의 긍정적 연결고리가 형성될 수 있다는 것이다(Mendonça, Cheng, Mélo, & de Farias Júnior, 2014). 이러한 긍정적 연결은 청소년들의 신체활동 참가와 관련한 많은 선행연구(Giles-Corti & Donovan, 2002; Thompson, Humbert, & Mirwald, 2003)에서도 제안되었을 정도로 강력한 관계성을 지닌다.

더 중요한 점은 바로 이와 같은 관계적 차원의 신체활동 조건이 가능해지기 위해 필요한 ‘환경적 차원’의 요소들이다. 신체활동에 활발하게 참여할 수 있도록 제반 사항이 마련되어야 한다는 점(물리적 환경), 그 환경에 여학생들이 참여할 수 있도록 공간적, 시간적 기회가 제공되어야 한다는 점(기회), 나아가 주어지는 신체활동의 기회 자체가 여학생들이 다루기 적합한 프로그램으로 구성되어야 한다는 점(적합성) 등이 연구모형에서 환경적 차원을 구성하는 요인으로 배치되었다. 물론 본 연구의 결과에는 신체활동의 종합적 모델을 고민한 다른 연구에서 보여준(eg., Spence & Lee, 2003) 신체활동에 대한 사회적 가치나 평가체계 같은 일종의 ‘문화적 체계’는 포함되지 못했지만, 여학생들에게 친화적인 신체활동 환경을 마련하는데 있어 기본적으로 갖추어야 할 조건이 구체적으로 포함되었다.

결론적으로, 여학생들의 신체활동 참가촉진요인 여섯 가지 범주는 다음과 같이 요약될 수 있다. “여학생들이 신체활동에 적극적으로 참가하게끔 하려면, 무엇보다 그들이 신체활동과 자신이 잘 어울릴 수 있다고 인정하게 만들어야 하고, 그것을 위해서는 여학생들이 중요하게 생각하는 중요타자와의 관계형성과 그들로부터의 사회적 지지를 이끌 수 있도록 만들어야 할 뿐 아니라, 이러한 관계가 원만히 형성되도록 여학생들의 신체활동 기회 자체를 양적으로 확장하며, 그 기회 속에 포함된 신체활동 프로그램 역시 여학생들이 다룰 수 있게끔 적합하게 만들어야 한다.” 즉, 모든 환경적, 관계적 차원의 참여촉진요인은 여학생들이 신체활동에 대해 지니는 ‘주도적 선택권(subjective selection)’을 증진하는 방향으로 작동되어야 한다.

참여촉진과 반대로, 신체활동 저해요인을 설명한 모형은 여학생들의 신체활동이 자신의 주체적인 인정과 달리, 신체활동과 관련한 자신의 평가를 ‘타자’에게 의존할 때 저해될 수 있음을 보여준다. 특히 자신의 외모를 타인의 시선, 특히 남학생들의 시선에 맞추어 생각하는 일종의 ‘객체화(objectification)’ 상태가 여학생들이 신체활동 참가를 주저하게 만드는 개인적 차원의 주요 범주가 될 것이라는 주장이다(Azzarito, 2009; Cockburn & Clarke, 2002). 물론 그처럼 내면화된 시선과 외모신경과 같은 개인적 차원의 저해요소를 야기한 근원적인 요인은 환경적 차원의 ‘여성적 규범’으로 볼 수 있겠다(Evans, 2006; Olafson, 2002). 그것이 관계적 차원에서 중요타자들로 하여금 여학생들의 신체활동에 대하여 부정적인 피드백을 하도록 만들고, 그러한 피드백을 받은 여학생들은 신체활동과 관련한 타자의 평가와 시선을 체화하며 이를 문화적 차원으로 확장시킨다는데, 이러한 메커니즘은 여학생들 뿐 아니라 여성코치의 경우에도 해당된다(cf., LaVoi & Dutove, 2012).

결국, 해외연구에서 종합적으로 밝혔듯, 여학생들의 신체활동 저해요인에서의 근원은 환경적 차원에서 가장 중요하게 도출된 ‘여성적 규범’이란 요인으로 나타났다. 즉, 여성에게 스포츠와 같은 신체활동이 어울리지 않는다는 문화적 규범으로 인해 위아래로 배치된 ‘기회의 제약’이 발생하고, ‘여성은 경쟁과 어울리지 않는다’는 규범으로도 이어진다. 여학생에게 적게 주어지는 신체활동 기회는 결국 그들로 하여금 다른 대안적 활동을 찾도록 만들고(대체활동), 스포츠가 지니는 경쟁성은 여성과 어울리지 않기에 부정적인 감정과 위험성으로 지각되면서 신체활동 참가를 저해하는 경로로 이어진다.

결론적으로, 여학생의 신체활동을 저해하는 요인은 “환경적 차원의 ‘여성적 규범’을 중심으로, 그것이 기회의 제약과 스포츠의 경쟁성을 강화하고, 이러한 환경에 사회화된 사람들은 여학생들에게 신체활동과 관련한 부정적 피드백을 주도록 체화되면서 여학생들에게 신체활동에 대한 타인의 시선과 외모평가를 내재화하는 방향으로 구조화한다”는 방식으로 명제화될 수 있다.

이들 가설적 모형은 여학생의 신체활동 참가를 증진하기 위해서 환경적, 관계적, 개인적 차원에서의 다양한 노력이 필요함을 말해준다. 환경적 차원에서는 여학생을 둘러싼 사회문화적, 물리적, 교육적 지원이 이루어져야 하고, 관계적 차원에서는 여학생이 일차적으로 만나는 부모, 친구, 교사와의 관계에서 긍정적 지지와 안정감을 얻어야함을 보여준다. 마지막으로 개인적 차원에서는 타인의 시선에서 벗어나 신체활동에 참가하는 자신을 긍정적으로 평가하는 경우 보다 적극적으로 신체활동에 참가할 수 있음을 본 가설적 모형은 설명해준다.

결론 및 제언

“여학생들이 체육수업에서 배제되거나 주변화되며 남학생들의 지배에 저항하지 못하는 것은 여학생들이 신체활동과 스포츠에 커다란 가치와 의미를 부여하지 않기 때문이다(Azzarito, et al., 2006, p. 223).”

이 연구는 여학생들에게 활발한 신체활동이 중요하다는 기본 전제를 바탕으로, 그들의 신체활동 증진을 위해 필요한 가설적 모형을 구축하고자 해외 선행연구를 종합적으로 분석하기 위한 목적을 지닌다. 보다 구체적으로, 우리보다 한 발 앞서 이 문제를 고민했던 해외연구의 결과물 중, 여학생들의 신체활동을 촉진시키는 요인과 저해하는 요인이 맥락별로 어떻게 나타나는가를 정리하여 종합적인 모델을 구성하기 위한 연구였다.

이를 위해 2005년부터 2016년까지 해외를 배경으로 여학생의 신체활동과 관련하여 이루어진 연구물 총 40편 중 신체활동 촉진과 저해요인이 명시된 26편을 대상으로 참가 촉진요인과 저해요인을 중심으로 분류하는 작업을 거쳤다. 그 이후 그것을 범주별로 묶어 개념화하고, 범주 간 관계를 도식화하는 작업을 진행하였다.

그 결과 여학생의 신체활동을 촉진하는 요인은 크게 여섯 가지로 요약되었다. 먼저 가장 중요하게 언급되었던 ‘자기인정(지)’을 시작으로, 신체활동과 관련된 주변 환경 조건으로서의 ‘물리적 환경’, 종목이나 시간의 선택을 가능케 하는 ‘기회’, 중요타자와의 지속적 상호작용을 전제하는 ‘관계형성’, 신체활동을 스스로 다룰 수 있는 조건으로서의 ‘적합성’, 마지막으로 부모나 교사, 친구에게 직간접적으로 받는 ‘사회적 지지’가 그것이다. 이들 요인들은 그 앞 자를 연결하여 ‘여학생의 신체활동 촉진요인으로서의 SPORTS’로 명명되었다. 이와는 달리, 여학생들의 신체활동을 저해하는 요인은 총 아홉 개로서, 구체적으로 ‘내면화된 시선’, ‘부정적 피드백’, ‘경쟁성’, ‘대체활동’, ‘위험 인지’, ‘외모 인식’, ‘불쾌한 감정’, ‘기회 부족’, ‘여성적 규범’으로 세분화되었다. 이들 아홉 개의 요인은 종합적으로 ‘여학생의 신체활동 저해요인으로서의 INCAPABLE’로 명명되었다.

이 연구의 결과가 우리에게 주는 흥미로운 결론은 여학생들의 신체활동 참가촉진과 저해가 궁극적으로 신체활동에 대한 판단 기준이 ‘자신’인가 ‘타자’인가에 따라 나타날 수 있음을 가설적 모형으로 구현했다는 점이다. 즉, 신체활동에 대한 주체적 해석이 이루어지는가, 아니면 타인의 평가에 종속되어 객체화되는가에 따라 여학생들의 신체활동 양상이 달라질 수 있음을 이론적으로 보여줬다는 것이다(eg., Beets, Pitetti, & Forlaw, 2007). 이러한 판단 기준에 영향을 미치는 요인으로 관계적 차원에서 중요타자의 부정적 피드백이나 사회적 지지가 작동하였고, 그것은 다시 ‘환경적 차원’에서의 다양한 신체활동 기회나 여성적 규범과 같은 물리적, 문화적 조건에 의해 주조되는 양상으로도 이어졌다.

이와 같은 연구의 결과는 여학생의 신체활동을 증진시켜야 할 국내 연구자 및 현장 전문가들이 무엇을 노력해야 할지 말해준다. 크게 세 가지 차원에서 그 노력의 지점과 방향을 요약해볼 수 있겠다.

첫째, 여학생의 주체화를 길러내기 위한 ‘주도적 선택권’을 만들어내야 한다는 고민이다. 여학생들이 주도적으로 신체활동을 선택할 기회 제공, 다양한 종목과 관계 지향적 성향을 고려한 수준별 수업 내용 구성이 필요한 지점이다. 또한 중요타자의 칭찬과 지원, 중요타자와 함께 신체활동에 참여하는 것은 여학생들이 타인의 시선이나 평가의 ‘대상(object)’이 되려는 수동적 태도를 바꾸는데 일조한다. 이는 여학생은 물론 중요타자의 인식을 바꾸는 노력이 될 수 있으며, ‘운동하는 여성에 대한 이미지’를 재정립시켜 사회문화적 편견을 바꾸어나가는 데도 도움이 된다. 이런 다차원적 노력은 여학생의 자존감과 유능감을 높여 ‘신체활동의 대상화’에서 벗어나 여학생들이 주체성을 증진하는 데 기여할 것이다.

둘째, 본 연구의 가설적 모형은 해외사례를 통해 구성된 것으로 추후 우리나라의 맥락을 고려한 모형으로 발전시키기 위한 고민이 필요하다. 우리나라의 사회문화적 환경 분석과 본 모형의 요인 관계 검증이 필요하다는 뜻이다. 이에 덧붙여 모형의 요인 간 관계를 보완할 필요도 있다. 지금까지는 ‘가설적’으로 맺어진 관계모형이기 때문이다. 향후 모형은 한국형 여학생 신체활동 촉진·저해요인을 중심으로 관계의 실증적 검증까지 더해져 좀 더 설명력이 강력한 모형으로 발전될 필요가 있다.

셋째, 여학생 신체활동과 관련된 연구에 있어서 다양한 접근의 필요성이다. 기존 여학생 신체활동 촉진 및 저해요인 관련 연구들은 대부분 설문지를 활용한 양적 방법으로 진행되었다. 물론 초기에 필요한 의미 있는 연구임에는 분명하지만, 이제는 접근의 다양성을 추구할 때이다. 예를 들어, 극단적으로 운동을 좋아하거나 운동을 싫어하는 여학생을 대상으로, 그러한 성향을 갖게 된 요인의 심층적 연구나, 학창시절 운동중독 수준으로 운동을 하던 여학생이 성인이 되었을 때 운동을 중단하게 된 경우나 반대로 운동을 싫어하던 여학생이 성인이 돼 운동을 좋아하게 된 계기에 대한 탐색적 종단 연구도 필요하다. 이러한 점에서 여성생애주기를 고려한 여성체육활성화 방안(Nam & Ha, 2011)이나 여성체육활성화 정책수립 방안 연구(Nam, Ju, Lee, Heo & Kim; 2017)는 그 기반이 되는 연구로 의미가 있다. 여학생 신체활동에 대한 다양한 관점의 연구가 누적되면 여성 생애주기별 신체활동 스펙트럼 및 이론적 모형으로 발전할 수 있을 것이다.

References

Azzarito, L. (2009). The panopticon of physical education: Pretty, active and ideally white. Physical Education and Sport Pedagogy, 14(1), 19-39.

Azzarito L.. 2009;The panopticon of physical education: Pretty, active and ideally white. Physical Education and Sport Pedagogy 14(1):19–39. 10.1080/17408980701712106.Azzarito, L., Solmon, M. A., & Harrison Jr, L. (2005). “...If I had a choice, I would....” A feminist poststructuralist perspective on girls in physical education. Research Quarterly for Exercise and Sport, 77(2), 222-239.

Azzarito L., Solmon M. A., et al, Harrison Jr L.. 2005;“...If I had a choice, I would....” A feminist poststructuralist perspective on girls in physical education. Research Quarterly for Exercise and Sport 77(2):222–239. 10.1080/02701367.2006.10599356.Bauer, K. W., Yang, Y. W., & Austin, S. B. (2004). “How can we stay healthy when you’re throwing all of this in front of us?” Findings from focus groups and interviews in middle schools on environmental influences on nutrition and physical activity. Health Education & Behavior, 31(1), 34-46.

Bauer K. W., Yang Y. W., et al, Austin S. B.. 2004;“How can we stay healthy when you’re throwing all of this in front of us?” Findings from focus groups and interviews in middle schools on environmental influences on nutrition and physical activity. Health Education & Behavior 31(1):34–46. 10.1177/1090198103255372.Beets, M. W., Pitetti, K. H., & Forlaw, L. (2007). The role of self-efficacy and referent specific social support in promoting rural adolescent girls’ physical activity. American Journal of Health Behavior, 31(3), 227-237.

Beets M. W., Pitetti K. H., et al, Forlaw L.. 2007;The role of self-efficacy and referent specific social support in promoting rural adolescent girls’ physical activity. American Journal of Health Behavior 31(3):227–237. 10.5993/AJHB.31.3.1.Beltrán-Carrillo, V. J., Devís-Devís, J., Peiró-Velert, C., & Brown, D. H. (2012). When physical activity participation promotes inactivity: Negative experiences of Spanish adolescents in physical education and sport. Youth & Society, 44(1), 3-27.

Beltrán-Carrillo V. J., Devís-Devís J., Peiró-Velert C., et al, Brown D. H.. 2012;When physical activity participation promotes inactivity: Negative experiences of Spanish adolescents in physical education and sport. Youth & Society 44(1):3–27. 10.1177/0044118X10388262.Biddle, S. J., Whitehead, S. H., O’Donovan, T. M., & Nevill, M. E. (2005). Correlates of participation in physical activity for adolescent girls: a systematic review of recent literature. Journal of Physical Activity and Health, 2(4), 423-434.

Biddle S. J., Whitehead S. H., O’Donovan T. M., et al, Nevill M. E.. 2005;Correlates of participation in physical activity for adolescent girls: a systematic review of recent literature. Journal of Physical Activity and Health 2(4):423–434. 10.1123/jpah.2.4.423.Carlson, T. B. (1995). We hate gym: Student alienation from physical education. Journal of teaching in Physical Education, 14(4), 467-477.

Carlson T. B.. 1995;We hate gym: Student alienation from physical education. Journal of teaching in Physical Education 14(4):467–477. 10.1123/jtpe.14.4.467.Casey, M. M., Eime, R. M., Payne, W. R., & Harvey, J. T. (2009). Using a socioecological approach to examine participation in sport and physical activity among rural adolescent girls. Qualitative Health Research, 19(7), 881-893.

Casey M. M., Eime R. M., Payne W. R., et al, Harvey J. T.. 2009;Using a socioecological approach to examine participation in sport and physical activity among rural adolescent girls. Qualitative Health Research 19(7):881–893. 10.1177/1049732309338198.Cockburn, C., & Clarke, G. (2002). “Everybody’s looking at you!”: Girls negotiating the “femininity deficit” they incur in physical education. Women’s Studies International Forum, 25(6), 651-665.

Cockburn C., et al, Clarke G.. 2002;“Everybody’s looking at you!”: Girls negotiating the “femininity deficit” they incur in physical education. Women’s Studies International Forum 25(6):651–665. 10.1016/S0277-5395(02)00351-5.Coleman, L., Cox, L., & Roker, D. (2008). Girls and young women’s participation in physical activity: Psychological and social influences. Health Education Research, 23(4), 633-647.

Coleman L., Cox L., et al, Roker D.. 2008;Girls and young women’s participation in physical activity: Psychological and social influences. Health Education Research 23(4):633–647. 10.1093/her/cym040.Dwyer, J. J., Allison, K. R., Goldenberg, E. R., & Fein, A. J. (2006). Adolescent girls’ perceived barriers to participation in physical activity. Adolescence, 41(161), 75-89.

Dwyer J. J., Allison K. R., Goldenberg E. R., et al, Fein A. J.. 2006;Adolescent girls’ perceived barriers to participation in physical activity. Adolescence 41(161):75–89.Eime, R. M., Payne, W. R., Casey, M. M., & Harvey, J. T. (2008). Transition in participation in sport and unstructured physical activity for rural living adolescent girls. Health Education Research, 25(2), 282-293.

Eime R. M., Payne W. R., Casey M. M., et al, Harvey J. T.. 2008;Transition in participation in sport and unstructured physical activity for rural living adolescent girls. Health Education Research 25(2):282–293. 10.1093/her/cyn060.Epstein, L. H. (1998). Integrating theoretical approaches to promote physical activity. American Journal of Preventive Medicine, 15(4), 257-265.

Epstein L. H.. 1998;Integrating theoretical approaches to promote physical activity. American Journal of Preventive Medicine 15(4):257–265. 10.1016/S0749-3797(98)00083-X.Evans, B. (2006). ‘I’d feel ashamed’: Girls’ bodies and sports participation. Gender, Place & Culture, 13(5), 547-561.

Evans B.. 2006;‘I’d feel ashamed’: Girls’ bodies and sports participation. Gender, Place & Culture 13(5):547–561. 10.1080/09663690600858952.Giles-Corti, B., & Donovan, R. J. (2002). The relative influence of individual, social and physical environment determinants of physical activity. Social Science & Medicine, 54(12), 1793-1812.

Giles-Corti B., et al, Donovan R. J.. 2002;The relative influence of individual, social and physical environment determinants of physical activity. Social Science & Medicine 54(12):1793–1812. 10.1016/S0277-9536(01)00150-2.Gillison, F., Sebire, S., & Standage, M. (2011). What motivates girls to take up exercise during adolescence? Learning from those who succeed. British Journal of Health Psychology, 17(3), 536-550.

Gillison F., Sebire S., et al, Standage M.. 2011;What motivates girls to take up exercise during adolescence? Learning from those who succeed. British Journal of Health Psychology 17(3):536–550. 10.1111/j.2044-8287.2011.02053.x.Grieser, M., Vu, M. B., Bedimo-Rung, A. L., Neumark-Sztainer, D., Moody, J., Young, D. R., & Moe, S. G. (2006). Physical activity attitudes, preferences, and practices in African American, Hispanic, and Caucasian girls. Health Education & Behavior, 33(1), 40-51.

Grieser M., Vu M. B., Bedimo-Rung A. L., Neumark-Sztainer D., Moody J., Young D. R., et al, Moe S. G.. 2006;Physical activity attitudes, preferences, and practices in African American, Hispanic, and Caucasian girls. Health Education & Behavior 33(1):40–51. 10.1177/1090198105282416.Gruno, J., & Gibbons, S. L. (2016). An exploration of one girl’s experiences in elective physical education: Why does she continue? Alberta Journal of Educational Research, 62(2), 150-167.

Gruno J., et al, Gibbons S. L.. 2016;An exploration of one girl’s experiences in elective physical education: Why does she continue? Alberta Journal of Educational Research 62(2):150–167.Hallal, P. C., Victora, C. G., Azevedo, M. R., & Wells, J. C. (2006). Adolescent physical activity and health. Sports Medicine, 36(12), 1019-1030.

. Hallal P. C., Victora C. G., Azevedo M. R., et al, Wells J. C.. 2006;Adolescent physical activity and health. Sports Medicine 36(12):1019–1030. 10.2165/00007256-200636120-00003.Han, T. R. (2010). A survey of current status and activation of girls’ physical activities participation. Korea Institute of Sport Science, report 3.

Han T. R.. 2010. A survey of current status and activation of girls’ physical activities participation Korea Institute of Sport Science. report 3.Hills, L. A. (2006). Playing the field (s): An exploration of change, conformity and conflict in girls’ understandings of gendered physicality in physical education. Gender and Education, 18(5), 539-556.

Hills L. A.. 2006;Playing the field (s): An exploration of change, conformity and conflict in girls’ understandings of gendered physicality in physical education. Gender and Education 18(5):539–556. 10.1080/09540250600881691.Hills, L. (2007). Friendship, physicality, and physical education: An exploration of the social and embodied dynamics of girls’ physical education experiences. Sport, Education & Society, 12(3), 317-336.

Hills L.. 2007;Friendship, physicality, and physical education: An exploration of the social and embodied dynamics of girls’ physical education experiences. Sport, Education & Society 12(3):317–336. 10.1080/13573320701464275.Hong, J. H., & Lee, S. Y. (2008). The Avoidance of Physical Educations of High School Girls in Accordance with the Grades and Behavior Patterns. Journal of Sport Science Research, 26, 93-104.

Hong J. H., et al, Lee S. Y.. 2008;The Avoidance of Physical Educations of High School Girls in Accordance with the Grades and Behavior Patterns. Journal of Sport Science Research 26:93–104.Hohepa, M., Schofield, G., & Kolt, G. S. (2006). Physical activity: what do high school students think?. Journal of Adolescent Health, 39(3), 328-336.

Hohepa M., Schofield G., et al, Kolt G. S.. 2006;Physical activity: what do high school students think? Journal of Adolescent Health 39(3):328–336. 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2005.12.024.Hwang, E. R., & Hwang, C. S. (2013). A Study on the Actual State of Adolescent Girl Students Physical Activity and Improvement Method. Korean Journal of Physical Eduaction, 52(4), 283-291.

Hwang E. R., et al, Hwang C. S.. 2013;A Study on the Actual State of Adolescent Girl Students Physical Activity and Improvement Method. Korean Journal of Physical Eduaction 52(4):283–291.Jago, R., Brockman, R., Fox, K. R., Cartwright, K., Page, A. S., & Thompson, J. L. (2009). Friendship groups and physical activity: Qualitative findings on how physical activity is initiated and maintained among 10-11 year old children. International Journal of Behavioral Nutrition and Physical Activity, 6:4.

Jago R., Brockman R., Fox K. R., Cartwright K., Page A. S., et al, Thompson J. L.. 2009;Friendship groups and physical activity: Qualitative findings on how physical activity is initiated and maintained among 10-11 year old children. International Journal of Behavioral Nutrition and Physical Activity 6:4. 10.1186/1479-5868-6-4.Jin, Y. K. (2017). Girls school physical education policy, Where it is?. Korean Journal of Sports Science, 139, 70-79.

Jin Y. K.. 2017;Girls school physical education policy, Where it is? Korean Journal of Sports Science 139:70–79.Joo, J. M. (2015). Legal and Institutional Proposals to Realize Gender Equity in School Sports: Application of Title IX of the U.S. The Korean Association of Sports Law, 18(1), 65-93.

Joo J. M.. 2015;Legal and Institutional Proposals to Realize Gender Equity in School Sports: Application of Title IX of the U.S. The Korean Association of Sports Law 18(1):65–93.Jo, Y. W. (2013). Female high school students' change of perception and participation toward physical education through applying untegrated learning activities. M. D. Dissertation. Seoul University

. Jo Y. W.. 2013. Female high school students' change of perception and participation toward physical education through applying untegrated learning activities et al. Seoul University;Jung, H. W., & Kim, D. H. (2016). An Exploration of the Direction of Polices for Girls’ Physical Education Promotion: Focusing on the revision of the Physical Education Promotion Act. Korean Society of Sport Policy. 14(4), 199-215

. Jung H. W., et al, Kim D. H.. 2016;An Exploration of the Direction of Polices for Girls’ Physical Education Promotion: Focusing on the revision of the Physical Education Promotion Act. Korean Society of Sport Policy 14(4):199–215.KBS News(2018.02.17.). Gum Tae Sup’s proposal ‘Girls’ physical activity promotion act’. http://news.kbs.co.kr/news/view.do?ncd=3607034&ref=A

. KBS News. 2018. 02. 17. Gum Tae Sup’s proposal ‘Girls’ physical activity promotion act’ http://news.kbs.co.kr/news/view.do?ncd=3607034&ref=A .Kim, M. H., & LEE, G. I. (2008). An action research to improve girls’ participation in physical. Korean Journal of Physical Eduaction, 47(6), 303-313.

Kim M. H., et al, LEE G. I.. 2008;An action research to improve girls’ participation in physical. Korean Journal of Physical Eduaction 47(6):303–313.Kim, S. J. (2014). Legal Framework to Facilitate Female Students` Participation in Sports: Focusing on Title IX. The Korean Association of Sports Law, 17(4), 59-77.

Kim S. J.. 2014;Legal Framework to Facilitate Female Students` Participation in Sports: Focusing on Title IX. The Korean Association of Sports Law 17(4):59–77.Kirk, D. (2005). Physical education, youth sport and lifelong participation: The importance of early learning experiences. European Physical Education Review, 11(3), 239-255.

Kirk D.. 2005;Physical education, youth sport and lifelong participation: The importance of early learning experiences. European Physical Education Review 11(3):239–255. 10.1177/1356336X05056649.Knowles, A. M., Niven, A., & Fawkner, S. (2011). A qualitative examination of factors related to the decrease in physical activity behavior in adolescent girls during the transition from primary to secondary school. Journal of Physical Activity and Health, 8(8), 1084-1091.

Knowles A. M., Niven A., et al, Fawkner S.. 2011;A qualitative examination of factors related to the decrease in physical activity behavior in adolescent girls during the transition from primary to secondary school. Journal of Physical Activity and Health 8(8):1084–1091. 10.1123/jpah.8.8.1084.Knowles, A. M., Niven, A., & Fawkner, S. (2014). ‘Once upon a time I used to be active’: Adopting a narrative approach to understanding physical activity behaviour in adolescent girls. Qualitative Research in Sport, Exercise and Health, 6(1), 62-76.

Knowles A. M., Niven A., et al, Fawkner S.. 2014;‘Once upon a time I used to be active’: Adopting a narrative approach to understanding physical activity behaviour in adolescent girls. Qualitative Research in Sport, Exercise and Health 6(1):62–76. 10.1080/2159676X.2013.766816.Kwag, M. S., & Cho, O. Y. (2015). A Survey on the Perception of Adolescent Female Students toward School’s Physical Education Class. Journal of Korean Physical Education Association for Girls and Women, 29(2), 61-88.

Kwag M. S., et al, Cho O. Y.. 2015;A Survey on the Perception of Adolescent Female Students toward School’s Physical Education Class. Journal of Korean Physical Education Association for Girls and Women 29(2):61–88. 10.16915/jkapesgw.2015.06.29.2.61.LaVoi, N. M., & Dutove, J. K. (2012). Barriers and supports for female coaches: An ecological model. Sports Coaching Review, 1(1), 17-37.

LaVoi N. M., et al, Dutove J. K.. 2012;Barriers and supports for female coaches: An ecological model. Sports Coaching Review 1(1):17–37. 10.1080/21640629.2012.695891.Lee, B. J., Kim, D. H. & M, H. J. (2008). Educational meaning and experience context of girl students` self-conscious affects in physical education class. Korean Journal of Physical Education, 47(4), 161-172.

Lee B. J., Kim D. H., et al, M H. J.. 2008;Educational meaning and experience context of girl students` self-conscious affects in physical education class. Korean Journal of Physical Education 47(4):161–172.Lee, C. S. (2010). Understanding of Contributing or Constraining Factors of Physical Activity of Girls: An Analysis of Relative Effect of Socio-Cultural and Psychological Factors. Korea Sports Promotion Foundation. Research in Sports academy.

Lee C. S.. 2010. Understanding of Contributing or Constraining Factors of Physical Activity of Girls: An Analysis of Relative Effect of Socio-Cultural and Psychological Factors Korea Sports Promotion Foundation. Research in Sports academy.Lee, C. H. (2011). The Effects of PE Class Obstacles on Female Students' Involvement in Sports. The Journal of Institute of School Health & Physical Education, 18(1), 487-500.

Lee C. H.. 2011;The Effects of PE Class Obstacles on Female Students' Involvement in Sports. The Journal of Institute of School Health & Physical Education 18(1):487–500.Lee, J. K. (2015). Research regarding the Realization of Gender Equity in School Sports: Application of the Three-Part Test of Title IX. The Korean Association of Sports Law, 18(3), 115-140.

Lee J. K.. 2015;Research regarding the Realization of Gender Equity in School Sports: Application of the Three-Part Test of Title IX. The Korean Association of Sports Law 18(3):115–140.Lee, J. M., & Park, J. J. (2012). Exploring the High School Girls` Perceptions on and Participation Attitudes of PE Class through an Integrated Narrative PE activities. The Korean Association of Sport Pedagogy, 19(4), 183-203.

Lee J. M., et al, Park J. J.. 2012;Exploring the High School Girls` Perceptions on and Participation Attitudes of PE Class through an Integrated Narrative PE activities. The Korean Association of Sport Pedagogy 19(4):183–203.Lee, O. S. (2010). The In-School PE Programs for Girls' Health and Fitness. The Korean Association of Sport Pedagogy(academic publications). 95-110.

Lee O. S.. 2010;The In-School PE Programs for Girls' Health and Fitness. The Korean Association of Sport Pedagogy(academic publications) :95–110.Lenskyj, H. (1995). What’s sport got to do with it? Canadian Woman Studies, 15(4), 6-10.

Lenskyj H.. 1995;What’s sport got to do with it? Canadian Woman Studies 15(4):6–10.Loman, D. G. (2008). Promoting physical activity in teen girls: Insight from focus groups. MCN: The American Journal of Maternal/Child Nursing, 33(5), 294-299.

Loman D. G.. 2008;Promoting physical activity in teen girls: Insight from focus groups. MCN: The American Journal of Maternal/Child Nursing 33(5):294–299. 10.1097/01.NMC.0000334896.91720.86.Mendonça, G., Cheng, L. A., Mélo, E. N., & de Farias Júnior, J. C. (2014). Physical activity and social support in adolescents: A systematic review. Health Education Research, 29(5), 822-839.

Mendonça G., Cheng L. A., Mélo E. N., et al, de Farias Júnior J. C.. 2014;Physical activity and social support in adolescents: A systematic review. Health Education Research 29(5):822–839. 10.1093/her/cyu017.Ministry of Culture, Sports and Tourism(2016). 2016 National sport participation survey. seoul: MCST

. Ministry of Culture, Sports and Tourism. 2016. 2016 National sport participation survey seoul: MCST.Ministry of Education(2016). 2016 girls’ physical education promotion policy. Seoul: MOE

. Ministry of Education. 2016. 2016 girls’ physical education promotion policy Seoul: MOE.Nam, S. W., & Lee, C. S. (2005). A Necessity and Possibility of Law-Enacting for the Promotion in Physical Activity of Female. Journal of Korean Society for the Study of Physical Education, 10(2), 21-35.

Nam S. W., et al, Lee C. S.. 2005;A Necessity and Possibility of Law-Enacting for the Promotion in Physical Activity of Female. Journal of Korean Society for the Study of Physical Education 10(2):21–35.Nam, S. W., & Lee, C. S. (2006). Reproduction of Gender Through Physical Activities in School. Korean Journal of Sociology of Sport, 19(3), 441-458.

Nam S. W., et al, Lee C. S.. 2006;Reproduction of Gender Through Physical Activities in School. Korean Journal of Sociology of Sport 19(3):441–458.Nam, Y. S. (2012). Physical Activity’s Exercise Physiology Changes on Obesity, Stress, Brain Development of Middle and High School Students. Journal of Korean Physical Education Association for Girls and Women Seminar, 2012(2), 35-45.

Nam Y. S.. 2012;Physical Activity’s Exercise Physiology Changes on Obesity, Stress, Brain Development of Middle and High School Students. Journal of Korean Physical Education Association for Girls and Women Seminar 2012(2):35–45.Nam, Y. S., & Ha, S. W. (2011). Sports Policy Proposal for the Activation of Women’s Physical Activities with Consideration for Women’s Life Cycle. Journal of Physical Growth and Motor Development, 19(2), 153-159.

Nam Y. S., et al, Ha S. W.. 2011;Sports Policy Proposal for the Activation of Women’s Physical Activities with Consideration for Women’s Life Cycle. Journal of Physical Growth and Motor Development 19(2):153–159.Nam, Y. S., Ju, S. H., Lee, Y. S., Heo, H. M., & Kim, D. H. (2017). A Study on the Policy Establishment for the Promotion of Women’s Physical Activities. Journal of Korean Society of Sport Policy, 40, 95-108.

Nam Y. S., Ju S. H., Lee Y. S., Heo H. M., et al, Kim D. H.. 2017;A Study on the Policy Establishment for the Promotion of Women’s Physical Activities. Journal of Korean Society of Sport Policy 40:95–108.Niven, A., Henretty, J., & Fawkner, S. (2014). ‘It’s too crowded’: A qualitative study of the physical environment factors that adolescent girls perceive to be important and influential on their PE experience. European Physical Education Review, 20(3), 335-348.

Niven A., Henretty J., et al, Fawkner S.. 2014;‘It’s too crowded’: A qualitative study of the physical environment factors that adolescent girls perceive to be important and influential on their PE experience. European Physical Education Review 20(3):335–348. 10.1177/1356336X14524863.Olafson, L. (2002). ‘I hate phys. ed.’: Adolescent girls talk about physical education. Physical Educator, 59(2), 67-74.

Olafson L.. 2002;‘I hate phys. ed.’: Adolescent girls talk about physical education. Physical Educator 59(2):67–74.O’ Donovan, T., & Kirk, D. (2008). Reconceptualizing student motivation in physical education: An examination of what resources are valued by pre-adolescent girls in contemporary society. European Physical Education Review, 14(1), 71-91.

O’ Donovan T., et al, Kirk D.. 2008;Reconceptualizing student motivation in physical education: An examination of what resources are valued by pre-adolescent girls in contemporary society. European Physical Education Review 14(1):71–91. 10.1177/1356336X07085710.Ryu, C. O. (2014). A case study- 3(Three)Station Handball Game Instruction for Activating Female Physical Education Class. Woori Physical Education, 11, 58-65.

Ryu C. O.. 2014;A case study- 3(Three)Station Handball Game Instruction for Activating Female Physical Education Class. Woori Physical Education 11:58–65.Sallis, J.F. & McKenzie, T.L. (1991). Physical education’s role in public health. Research Quarterly for Exercise and Sport, 64, 25-31.

Sallis J.F., et al, McKenzie T.L.. 1991;Physical education’s role in public health. Research Quarterly for Exercise and Sport 64:25–31. 10.1080/02701367.1993.10608775.Shannon, C. S. (2016). Exploring factors influencing girls’ continued participation in competitive dance. Journal of Leisure Research, 48(4), 284-306.

Shannon C. S.. 2016;Exploring factors influencing girls’ continued participation in competitive dance. Journal of Leisure Research 48(4):284–306. 10.18666/JLR-2016-V48-I4-6601.Slater, A., & Tiggemann, M. (2010). “Uncool to do sport”: A focus group study of adolescent girls’ reasons for withdrawing from physical activity. Psychology of Sport and Exercise, 11(6), 619-626.

Slater A., et al, Tiggemann M.. 2010;“Uncool to do sport”: A focus group study of adolescent girls’ reasons for withdrawing from physical activity. Psychology of Sport and Exercise 11(6):619–626. 10.1016/j.psychsport.2010.07.006.Spence, J. C., & Lee, R. E. (2003). Toward a comprehensive model of physical activity. Psychology of Sport and Exercise, 4(1), 7-24.

Spence J. C., et al, Lee R. E.. 2003;Toward a comprehensive model of physical activity. Psychology of Sport and Exercise 4(1):7–24. 10.1016/S1469-0292(02)00014-6.Spencer, R. A., Rehman, L., & Kirk, S. F. (2015). Understanding gender norms, nutrition, and physical activity in adolescent girls: A scoping review. International Journal of Behavioral Nutrition and Physical Activity, 12:6.

Spencer R. A., Rehman L., et al, Kirk S. F.. 2015;Understanding gender norms, nutrition, and physical activity in adolescent girls: A scoping review. International Journal of Behavioral Nutrition and Physical Activity 12:6. 10.1186/s12966-015-0166-8.Standiford, A. (2013). The secret struggle of the active girl: a qualitative synthesis of interpersonal factors that influence physical activity in adolescent girls. Health Care for Women International, 34(10), 860-877.

Standiford A.. 2013;The secret struggle of the active girl: a qualitative synthesis of interpersonal factors that influence physical activity in adolescent girls. Health Care for Women International 34(10):860–877. 10.1080/07399332.2013.794464.Stankov, I., Olds, T., & Cargo, M. (2012). Overweight and obese adolescents: What turns them off physical activity?. International Journal of Behavioral Nutrition and Physical Activity, 9: 53.

Stankov I., Olds T., et al, Cargo M.. 2012;Overweight and obese adolescents: What turns them off physical activity? International Journal of Behavioral Nutrition and Physical Activity 9:53. 10.1186/1479-5868-9-53.Svender, J., Larsson, H., & Redelius, K. (2012). Promoting girls’ participation in sports: discursive constructions of girls in a sports initiative. Sport, Education & Society, 17(4), 463-478.

Svender J., Larsson H., et al, Redelius K.. 2012;Promoting girls’ participation in sports: discursive constructions of girls in a sports initiative. Sport, Education & Society 17(4):463–478. 10.1080/13573322.2011.608947.The National Coalition for Women and Girls in Education(2012). Title IX and Sports: Proven Benefits, Unfounded Objections. NCGS.

. The National Coalition for Women and Girls in Education. 2012. Title IX and Sports: Proven Benefits, Unfounded Objections NCGS.Thompson, A. M., Humbert, M. L., & Mirwald, R. L. (2003). A longitudinal study of the impact of childhood and adolescent physical activity experiences on adult physical activity perceptions and behaviors. Qualitative Health Research, 13(3), 358-377.

Thompson A. M., Humbert M. L., et al, Mirwald R. L.. 2003;A longitudinal study of the impact of childhood and adolescent physical activity experiences on adult physical activity perceptions and behaviors. Qualitative Health Research 13(3):358–377. 10.1177/1049732302250332.United Nations(2005). International Year of Sport and Physical Education 2005. UN.

United Nations. 2005. International Year of Sport and Physical Education 2005 UN.U.S. Department of Education(2005). Additional clarification of intercollegiate athletics policy: Three-part test- part three. ED Pubs, Education publications Center

. U.S. Department of Education. 2005. Additional clarification of intercollegiate athletics policy: Three-part test- part three ED Pubs, Education publications Center.van Daalen, C. (2005). Girls’ experiences in physical education: Competition, evaluation, & degradation. The Journal of School Nursing, 21(2), 115-121.

van Daalen C.. 2005;Girls’ experiences in physical education: Competition, evaluation, & degradation. The Journal of School Nursing 21(2):115–121. 10.1177/10598405050210020901.Vilhjalmsson, R., & Thorlindsson, T. (1998). Factors related to physical activity: a study of adolescents. Social Science & Medicine, 47(5), 665-675.

Vilhjalmsson R., et al, Thorlindsson T.. 1998;Factors related to physical activity: a study of adolescents. Social Science & Medicine 47(5):665–675. 10.1016/S0277-9536(98)00143-9.Vu, M. B., Murrie, D., Gonzalez, V., & Jobe, J. B. (2006). Listening to girls and boys talk about girls’ physical activity behaviors. Health Education & Behavior, 33(1), 81-96.

Vu M. B., Murrie D., Gonzalez V., et al, Jobe J. B.. 2006;Listening to girls and boys talk about girls’ physical activity behaviors. Health Education & Behavior 33(1):81–96. 10.1177/1090198105282443.Watson, D. B., Adams, J., Azevedo, L. B., & Haighton, C. (2016). Promoting physical activity with a school-based dance mat exergaming intervention: qualitative findings from a natural experiment. BMC Public Health, 16:609.

Watson D. B., Adams J., Azevedo L. B., et al, Haighton C.. 2016;Promoting physical activity with a school-based dance mat exergaming intervention: qualitative findings from a natural experiment. BMC Public Health 16:609. 10.1186/s12889-016-3308-2.Whitehead, S., & Biddle, S. (2008). Adolescent girls’ perceptions of physical activity: A focus group study. European Physical Education Review, 14(2), 243-262.

Whitehead S., et al, Biddle S.. 2008;Adolescent girls’ perceptions of physical activity: A focus group study. European Physical Education Review 14(2):243–262. 10.1177/1356336X08090708.Wright, M. S., Wilson, D. K., Griffin, S., & Evans, A. (2008). A qualitative study of parental modeling and social support for physical activity in underserved adolescents. Health Education Research, 25(2), 224-232.

Wright M. S., Wilson D. K., Griffin S., et al, Evans A.. 2008;A qualitative study of parental modeling and social support for physical activity in underserved adolescents. Health Education Research 25(2):224–232. 10.1093/her/cyn043.Yoo, S. S. (2002). An Analysis of Determinants for Formation of Negative Attitude toward Physical Education : Perspectives of Female College Students. The Korean Association of Sport Pedagogy, 9(1), 79-94.

Yoo S. S.. 2002;An Analysis of Determinants for Formation of Negative Attitude toward Physical Education : Perspectives of Female College Students. The Korean Association of Sport Pedagogy 9(1):79–94.Yu, E. U. & Kim, J. W. (2002). A Qualitative Study on Perception for the School Physical Education of Female Student. Korean journal of physical education, 41(2), 181-197.

Yu E. U., et al, Kim J. W.. 2002;A Qualitative Study on Perception for the School Physical Education of Female Student. Korean journal of physical education 41(2):181–197.Yungblut, H. E., Schinke, R. J., & McGannon, K. R. (2012). Views of adolescent female youth on physical activity during early adolescence. Journal of Sports Science & Medicine, 11(1), 39-50.

Yungblut H. E., Schinke R. J., et al, McGannon K. R.. 2012;Views of adolescent female youth on physical activity during early adolescence. Journal of Sports Science & Medicine 11(1):39–50.