심야운동 중 체온변이가 일주기 지연에 미치는 영향

Effects of body temperature variations during nocturnal exercise on circadian phase delay

Article information

Abstract

본 연구는 심야운동으로 인한 체온(Tb) 상승이 운동 중 상승하는 체온을 억제시킨 조건에 비해 일주기지연(circadian phase delay)을 더욱 심화시키는지 평가하였다. 일곱 명의 건강한 남자(20.57 ± 2.88 세, 174.43 ± 4.05 cm, 70.13 ± 6.07 kg, 체지방 10.74 ± 1.92%)가 두 번의 실험에 참여하였고 각각의 실험은 5일간 진행되었다. 각 실험의 첫날, 피험자들은 일상적인 취침시간(23:00-07:00, 0.2 lux)을 유지하였다. 2일째부터 5일째까지, 01:30부터(15 lux) 개인 최대능력의 55%에서 60분간 고정식자전거운동을 했다. 그리고 04:00에 취침하여 12:00에 기상하였다. 실험은 26℃ 환경에서 체온을 올리며 운동하거나(ET) 또는 17℃ 환경에서 체온상승을 억제하며 운동하는(ST) 것으로 진행되었다. 각 실험은 2주의 간격으로 균형 배정되었다. 운동 중 직장온, 피부온, 심박수가 지속적으로 기록되었다. 운동 전과 후에 체중이 측정되었으며 뇨량과 타액 샘플이 채취되었다. 각 실험의 첫날과 5일째 4번(23:00, 03:30, 07:00, 12:00) 혈액이 채취되어 멜라토닌이 분석되었다. 4일간의 심야운동으로 평균체중 감소량은 ET에서 0.62 ± 0.09 kg, ST에서 0.22 ± 0.07 kg으로 나타났다(p<.001). 직장온은 운동 중 증가하였으며 조건간의 차이는 없었다. 피부온은 ET에서 32℃, ST에서 24℃로 유지되었다(p<.001). 평균체온은 ST에 비해 ET에서 더 높았다(p<.05). 심야운동 중 총평균 뇨배출량은 ET에서 0.07 ± 0.07 liter, ST에서 0.11 ± 0.07 liter로 나타났다(p<.05). 첫날 멜라토닌 농도는 ET에서 시간별로 23 ± 26, 107 ± 45, 98 ± 46, 14 ± 50 pg/ml 였으며, ST에서는 18 ± 10, 108 ± 65, 103 ± 75, 14 ± 12 pg/ml 였다. 실험 5일째 멜라토닌은 ET에서 9 ± 3, 64 ± 41, 122 ± 73, 54.1 ± 17.8 pg/ml, ST에서 8 ± 1, 68 ± 21, 111 ± 52, and 32 ± 14 pg/ml로 나타났다. 멜라토닌은 실험 5일째 12:00시에 두 조건 간, 그리고 첫째 날과 5일째 12:00시 각 조건 내에서 차이를 보였다. 타액 코르티졸과 타액 IgA 는 차이가 없었다. 심야운동은 두 조건 모두에서 일주기지연을 유발하였다. 그러나 운동 중 체온상승이 지연을 강화시켰으며 이는 운동 중 열부하의 일주기이동에 미치는 영향의 중요성을 지적한다.

Trans Abstract

Whether a nocturnal exercise with concomitant increase of body temperature (Tb) would intensify circadian phase delay compare to exercise with a suppressed Tb increase was examined. Seven healthy men (20.57 ± 2.88 yrs, 174.43 ± 4.05 cm, 70.13 ± 6.07 kg, 10.74 ± 1.92% fat) participated in two tests. Each lasted 5-days. On the day of 1 of each test, subjects maintained habitual sleep time (23:00-07:00, 0.2 lux) in laboratory. From day 2 thru 5, they biked for 60 min at 55% of maximal capacity beginning at 01:30 (15 lux). Then they went to bed at 04:00 and woke at 12:00. During test, they exercised either at 26℃ with elevating Tb (ET) or at 17℃ with cooling devices for suppressing Tb (ST). Two tests were counter balanced and separated by 2 weeks. During exercise, rectal (Tre) and skin (Tsk) temperatures, and heart rate were continuously recorded. Body weight changes during exercise were measured. Urine volume and saliva sample were collected. Blood samples were taken at 23:00, 03:30, 07:00, and 12:00 on day 1 and 5 of tests and analyzed for melatonin. The average weight loss for 4 days of exercise in ET and ST was 0.62 ± 0.09 and 0.22 ± 0.07 kg, respectively (p<.001). Tre increased during exercise but not different between conditions. Tsk maintained at 32℃ in ET and 24℃ in ST (p<.001). Tb were higher in ET than ST during exercise (p<.05). The average total urine volume passed was 0.07 ± 0.07 in ET and 0.11 ± 0.07 liter in ST (p<.05). The melatonin concentration at day 1 was 23 ± 26, 107 ± 45, 98 ± 46, and 14 ± 5 in ET and 18 ± 10, 108 ± 65, 103 ± 75, and 14 ± 12 pg/ml in ST for each time period. At day 5, it was 9 ± 3, 64 ± 41, 122 ± 73, and 54.1 ± 17.8 in ET and 8 ± 1, 68 ± 21, 111 ± 52, and 32 ± 14 pg/ml in ST. Differences of melatonin between ET and ST at day 5 of 12:00 as well as between day 1 and 5 at 12:00 of both conditions were noticed (p<.05). Salivary cortisol and immunoglobulin-A were not different. A nocturnal exercise induced a circadian phase delay in both conditions. However, body temperature increase during exercise intensified the shift indicating the importance of thermal load during exercise for circadian shift.

서론

설치류를 포함한 포유류(Ellis et al., 1982; Reebs & Mrosovsky, 1989; Turek, 1989; Wickland & Turek, 1991)와 인간은(Aschoff et al., 1971; Buxton et al., 2003; Van Reeth et al., 1994) 일주기이동(circadian phase shift) 능력을 갖는다. 현재까지 일주기이동을 가능하게 한다는 다양한 자극들에는 빛(Shanahan et al., 1999), 반복적인 사회적신호(social cues)(Aschoff et al., 1971; Smith et al., 1992), 신체활동(Buxton et al., 2003), 식사시간, 시간에 대한 인지(Atkinson et al., 2007), 청각적 자극(Goel, 2005), 호르몬처방(Hack et al., 2003) 등이 제시되고 있다.

지금까지의 연구들은 인간이 신체적 운동을 통해 호르몬 주기의 변화를 동반한 일주기이동이 현저하게 나타날 수 있음을 보고하고 있다(Barger et al., 2004; Buxton et al., 2003; Miyazaki et al., 2001; Van Reeth et al., 1994). Eastman et al.(1995)은 3시간의 심야운동 후 멜라토닌과 항갑상선호르몬(antithyroid hormones)의 급상승지연(delayed surge)을 증명하였고 Barger 등(2004) 또한 15일간의 심야운동이 밤중의 멜라토닌 분비를 감소시켰다고 보고하였다. 멜라토닌의 분비와 체온의 파동에 대한 연구들은 체온이 감소하기 시작하는 02:00시에 운동을 함으로써 체온상승이 유발되고 멜라토닌 분비가 강력하게 억제되어 주기지연이 유발된다는 것이다(Barger et al., 2004; Miyazaki et al., 2001). 상대적으로 2주간의 낮 또는 오후 시간대의 중등강도 운동은 주기단축(phase advance)의 결과를 나타냈다(Miyazaki et al., 2001). 이러한 결과들은 운동 시간대가 일주기 파동에 중요한 역할을 수행하고 있음을 보여준다. 즉 주기단축과 주기지연은 하루 중 어느 시간대에 운동을 하는가에 영향을 받는다는 것이다.

운동 지속 시간 및 운동 시간대 이외에 운동강도 또한 주기이동에 영향을 미치는 것으로 알려진다. 운동에 의한 급성 시상하부-뇌하수체-부신 축의 자극을 위해서는 개인 최대능력의 약 50% 이상에 해당하는 운동 강도가 요구된다(Smoak et al., 1991). 이것은 일주기이동의 지표로 사용되는 호르몬 수치의 변화를 유발하기 위해서는 적정한 운동강도가 적용되어야 한다는 것이다. Buxton et al.(1997)은 건강한 남성들을 대상으로 낮은 강도(최대능력의 40%)와 높은 강도(최대능력의 75%)의 심야운동을 번갈아 실시하도록 하였다. 결과적으로 두 운동 모두에서 높은 갑상선호르몬 수치가 나타났고, 강한 운동에서 더 높은 멜라토닌 수치가 나타났다. Monteleone 등(1992)의 연구에서도 개인 최대 능력의 50%에 이은 80%에서의 야간운동이 멜라토닌의 수치감소와 코티졸(cortisol)의 수치상승이 관찰되었다. 이러한 결과들은 개인의 호르몬 리듬과 수면리듬의 관계를 입증하는 것으로 운동의 강도와 시간이 영향을 미칠 수 있음을 나타낸다.

운동은 단지 근육의 수축과 이완으로 나타나는 신체적 움직임만으로 특징 지워지거나, 또는 운동이 시간과 강도와 같은 정량지표만으로 평가되어 그 효과에 대한 고찰이 이루어지는 것은 아니다. 운동은 동시에 신경계와 내분비계를 자극하고 체온변화도 유발한다. 운동은 수면을 유발하는 멜라토닌의 분비양상을 변화시키기도 하며 그 효과의 지속시간에까지 영향을 미친다(Atkinson & Reilly, 1996). Buxton 등(2003)은 심야운동을 시행한 날의 멜라토닌 분비는 변화를 나타내지만, 이것이 다음 날까지 일정하게 지속되는 것은 아니라고 하였다. 일회적 운동 후 주기이동 양상이 나타날 수도 있지만 2일, 3일 후에는 다시 원래의 일주기적 리듬으로 되돌아간다고 설명하고 있다. 즉 일회적 운동에 의한 멜라토닌 분비의 변화는 일시적인 현상에 불과하며, 이를 지속하기 위해서는 규칙적인 일주기 지연이 필요하다고 보고되고 있다(Eastman et al., 1995).

그러나 현재까지 심야운동으로 인한 주기지연이 운동자극 자체에 의한 것인지 아니면 운동으로 인한 체온변화와 함께 그 영향을 나타내는 것인지 밝혀진 바가 없다. 운동은 신경계와 내분비계의 교란과 반응을 유도하지만, 동시에 체온의 상승을 유발하기도 한다. 이전의 연구들이 운동 시간대나 강도에 따른 일주기 이동을 설명하고 있지만 운동으로 동반하는 체온변화를 따로 분리하여 평가하지는 않았다. 만약 운동자극과 체온변화를 서로 다른 변인으로 분리한다면 두 요인이 주기이동에 어느 정도의 영향을 미치는지 알아볼 수 있을 것이다. 따라서 본 연구는 심야운동 중 체온의 상승을 자연스럽게 허용한 조건과 체온상승을 억제하는 조건에서 주기이동이 어떻게 나타나는지를 평가하는데 목적을 두었다. 선행된 연구에 근거하여 심야운동은 일주기를 지연시킬 것으로 예상되며, 운동과 동반되는 체온상승을 억제한 경우 일주기지연의 위축될 것으로 예상된다.

연구방법

연구대상자

7명의 건강한 남자대학생이 연구에 참여하였다. 이들은 자발적으로 연구참여동의서에 서명하였으며, 병력기록지를 통해 정신적, 내분비계적, 대사적질환이 없는 것으로 나타났다. 이들은 약 24:00에서 01:00 시에 잠자리에 들어 07:00에서 08:00 시 사이에 잠에서 깨는 수면주기를 유지하고 있었다. 불면증을 보고한 대상자는 없었다. 운동선수, 흡연자, 알코올이나 카페인과 같은 주기적 약물 복용자, 야간근무자, 또는 최근 6주 이내 2시간 이상의 시차를 가진 지역에 여행을 다녀온 자도 연구 참여에서 제외되었다. 이들의 연령은 20.57 ± 2.88 세, 신장은 174.43 ± 4.05 cm, 체중은 70.13 ± 6.07 kg, 체질량지수는 23.11 ± 2.08 kg/m2, 체지방률은 10.74 ± 1.92%, 안정시심박수는 63.86 ± 9.6 beat·min-1, 최대심박수는 177.71 ± 14.17 beat·min-1였다.

실험설계

본 연구는 사전평가와 두 번의 실험이 진행되었다. 사전평가에서는 신체측정과 최대유산소능력이 평가되었다. 각 실험에서 대상자들은 4일 연속 심야운동을 수행하였다. 한 번의 실험은 26℃(ET)의 실내온도에서 체온상승을 허용하는 조건으로, 다른 한 번의 실험은 17℃(ST)의 실내온도에서 체온상승을 억제하는 조건으로 운동을 했다. 각 실험은 5일(약 113시간) 동안 진행되었다. 첫날 대상자들은 23:00시에 취침하였으며 다음날 07:00시에 기상하였다. 둘째 날, 대상자들은 01:30시부터 60분간 개인 최대운동수행능력의 55%로 자전거 에르고미터운동을 실시하였다. 4일간의 심야운동은 일주기이동을 위한 최소한의 기간으로 설정되었다(Buxton et al., 2003; Lewy et al., 1998). 심야운동이 있는 날, 대상자들은 04:00시에 취침하여 같은 날 12:00에 기상하였다. 두 실험은 2주간의 간격을 두었으며 순서는 균형 배정되었다.

사전평가

대상자의 신장, 체중, 피하지방두께(3군데; 가슴, 복부, 대퇴)가 측정되었으며 신체질량지수와 체지방률이 환산되었다(Jackson & Pollock, 1978). 앉은 자세에서 10분간 안정 후 전자심박수측정계(Polar S610i, PolarElectro, Kempele, Finland)를 이용해 안정시심박수가 측정되었다.

개인의 최대유산소능력은 자전거에르고미터(Monark 828E, Monark Exercise AB, Vansbro, Sweden)를 이용해 점증운동부하방식으로 평가되었다. 운동시간 및 강도는 중량 2 kp로 2분간 운동한 후 매 2분마다 1 kp 증가시켰으며 페달링은 50 rpm을 유지하도록 하였다(Heyward, 2006). 운동종료는 자발적으로 기권을 표현한 시점이었고 평균운동시간은 8분 34초(±36초)이었다. 운동 중 지속적으로 심박수가 측정되었으며 운동종료 바로 직전의 심박수를 최대심박수로 평가하였다. 최대유산소능력 평가 후 30분간, 또는 안정시심박수가 돌아올 때까지 휴식을 취하였다. 이후 본 실험에 적용할 개인최대능력의 55%의 운동강도를 설정하였다. 운동강도 설정은 대상자들이 에르고미터에서 저항 없이 60rpm으로 2분 동안 운동한 후 점증적으로 저항을 증가시켜 자신의 목표심박수에 근접하는 운동부하양을 찾는 방법으로 진행되었다. 목표심박수에서 3분간 유지된 경우 이 기간의 운동부하양이 이후의 실험에서 사용하는 운동강도로 결정되었다.

실험절차

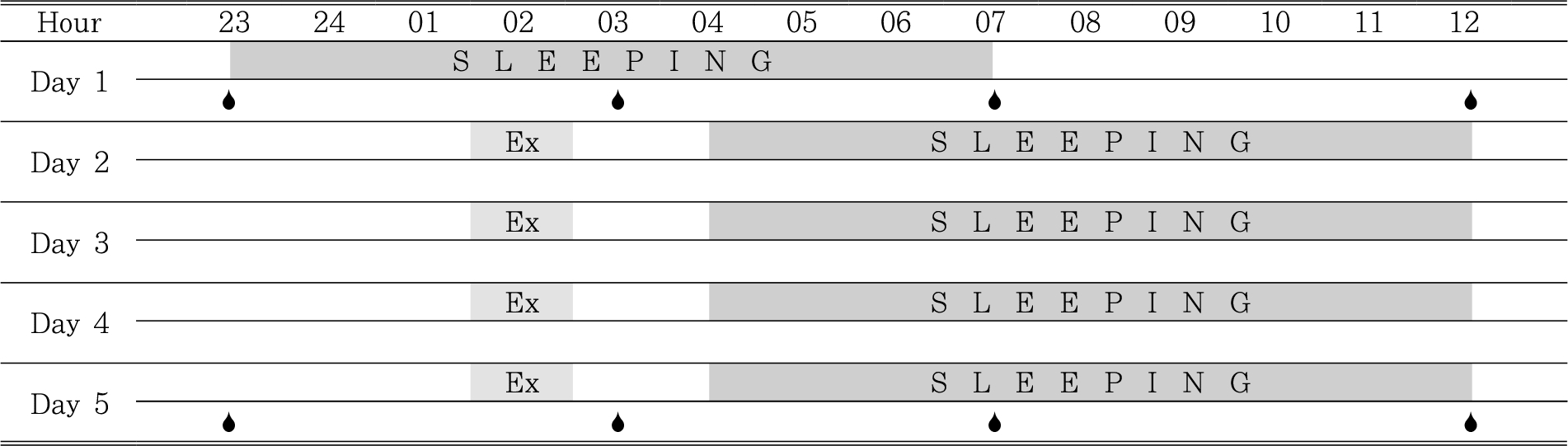

실험절차는 <그림 1>에서 보여주고 있다. 실험이 시작하기 일주일 전부터 정상적인 수면주기를 유지하도록 요청하였으며, 약 23:00시에 취침하여 7시간의 수면시간을 유지하도록 하였다. 이 기간 동안 가능한 격한 운동을 삼가도록 하였으며 낮잠도 피하도록 하였다.

Schematic representation of experimental schedule.

Each subject underwent this procedure twice separated by 15 days.

Ex: exercise session, 💧: blood sampling.

실험 첫날, 저녁식사 후 20:00시에 실험실에 도착하여 편한 휴식을 취하였다. 약 30분간의 안정 후 23:00시에 첫 번째 혈액샘플이 채취되었다. 채취 후 곧바로 취침하였으며, 03:30시에 약 10분간 기상하여 두 번째 혈액샘플이 채취되었다. 아침 07:00시에 기상하여 세 번째 혈액샘플이 채취되었다. 이후 실험실을 떠나 오전 일과를 마치고 12:00시 다시 실험실에 방문하여 네 번째 혈액샘플이 채취되었다. 그리고 오후 일정을 마치고 23:00시에 실험실로 돌아왔다.

실험실에 돌아온 후 취침과 누워있는 것을 제한하였으며, 대부분 TV를 시청하거나 컴퓨터와 시간을 보냈다. 자정 이후 01:00시에 대소변 배출 후 알몸 체중을 쟀으며, 직장온도센서(thermocouple, Barnant, MA, USA)를 항문으로부터 10cm 깊이로 삽입하였다. 심박수를 위한 전자심박수측정계를 차고 피부온도센서(thermocouple, Barnant, MA, USA)를 세군데(가슴, 윗팔, 허벅지)에 테이프를 이용해 부착시켰다. 타액 채취도 이루어졌다. 대상자들은 수돗물로 입안을 행군 후 증류수로 다시 입안을 헹구었다. 살균 처리된 길이 3cm, 지름 0.8cm의 타액 분비 자극물질이 포함된 면봉(Salivett)을 약 1분 동안 씹어 면봉이 타액으로 충분히 적셔지도록 하였다. 적셔진 면봉은 지정된 용기에 수거되어 원심 분리되었다. 그리고 반바지와 신발을 신고 01:30시부터 미리 정해진 운동강도로 60분간 운동을 시작하였다. 운동 전과 후 다리 스트레칭을 실시하였다. ET에서 실내온도는 26℃로 유지되었으며, 체온조작은 이루어지지 않았다. 반면 ST에서는 선풍기와 얼음조각을 집어넣은 냉각소품을 이용하여 체온 상승을 적극적으로 무마시켰다. 운동이 끝난 후, 피부의 물기를 모두 닦아냈으며 바로 알몸체중을 측정하였고 대상자들은 샤워 후 잠자리에 들었다. 취침은 04:00시부터 시작하였다. 운동 중 광도는 15룩스(YL102, UiNs, 대만)를 유지하였으며, 침실은 0.5룩스로 유지하였다(Barger et al., 2004).

대상자들은 12:00시에 기상하였다. 대상자들은 첫날과 똑같은 일정을 3일간 진행하였다. 네 번째 심야운동에서 이들의 혈액채취가 이전의 실험에서와 같은 시간과 방식으로 이루어졌다.

측정 및 환산

운동 중 심박수는 매 5분 간격으로 기록되었다. 피부온과 직장온은 지속적으로 관찰되었으며 안정시 온도와 이후 15분 간격의 온도가 데이터 저장장치(#692-0230, Barnant, MA, USA)에 로그인되었다. 평균피부온은 0.43⨯가슴피부온+0.25⨯윗팔피부온+0.32⨯허벅지피부온(Roberts et al., 1977)으로, 평균체온은 0.67⨯직장온+0.33⨯평균피부온으로 환산(Vallerand & Jacobs, 1989)되었다. 운동 중 발생한 체중변화도 환산되었다. 심박수, 직장온, 평균피부온, 평균체온의 측정 시기는 안정, 운동 15분, 운동 30분, 운동 45분, 운동 60분으로 총 5회 이었다.

혈액 및 타액분석

매회 혈액샘플은 일회용 실린지를 이용해 채취되었으며, EDTA가 포함된 5 ml 의 튜브에 담겨졌다. 원심분리기를 이용해 혈장이 분리되었으며, 혈장은 분석이 이루어질 때까지 –35℃로 냉동보관 되었다. 혈장 멜라토닌(melatonin)은 radioimmunoassay 방식을 이용하였으며, 시약(IBL)을 사용해 r-counter(COBR 5010 Quantum, PACKARD, USA)로 분석되었다. 젖산은 각 조건에서 마지막 날 진행된 운동 직후 측정되었다. 약 2-3 ml의 분리된 타액은 –35℃로 냉동보관 되었다가 EIA 방법을 이용하여 코티졸과 immunoglobulin-A(S-IgA)를 분석하는데 사용되었다.

통계분석

본 연구에서 얻어진 결과수치들은 Window용 SPSS Win 17.0 프로그램을 이용하여 통계적으로 분석되었다. 모든 수치들은 평균과 표준편차로 나타내었다. 두 조건에서 체온변인과 심박수 반응, 멜라토닌, S-IgA의 수치는 이원변량분석 반복측정법(2-way ANOVA with repeated measures)를 이용하여 비교되었다. 체중변화, 뇨배출량, 젖산수치는 대응표본 t 검정을 이용하였다. 통계적 유의수준은 p<.05 로 설정하였다.

결과

체중변화

심야운동에 의한 체중의 변화량은 ET에서 –0.62 ± 0.09 kg, ST에서 –0.22 ± 0.07 kg 였으며, 통계적으로 차이를 나타냈다(p<.001). 각 조건에서 뇨배출량은 ET에서 0.07 ± 0.07 리터, ST에서 0.11 ± 0.07 리터였다(p>.05).

체온변인 및 심박수 반응

<그림 2>에서는 심야운동 중 각 조건에서 4일간의 평균피부온, 직장온, 평균체온과 심박수 반응을 보여주고 있다. 운동이 진행되면서 ST가 ET에 비해 평균피부온 약 7-8℃, 평균체온 약 2-3℃, 심박수 약 6-8 beat·min-1 낮게 나타났다. 통계적으로는 평균피부온과 평균체온에서 두 조건 간에 차이를 나타냈다(p<.05). 직장온과 심박수는 두 조건 간에 차이를 보이지 않았다.

혈액 및 타액 변인 반응

심야운동 마지막 날의 운동 직후 채취된 혈액의 젖산농도는 ET에서 4.3 ± 0.35 mmol/dL, ST에서 4.0 ± 0.40 mmol/dL 로 나타났으며, 통계적 차이는 없었다(p>.05). 심야운동 첫날의 멜라토닌은 <그림 3-A>에서, 마지막 날의 수치는 <그림 3-B>에서 보여주고 있다. 03:30 시에서, 5일째의 멜라토닌 분비량은 첫날의 분비량에 비해 낮았다(p<.05). 12:00 시에, 첫날에 비해 5일째 두 조건 모두에서 멜라토닌의 분비량은 증가하였다. 또한 5일째 12:00 시에, 멜라토닌 분비량은 ST 보다 ET 에서 높게 나타났다(p<.05).타액 S-IgA는 <그림 4>에서, 타액 코티졸은 <그림 5>에서 보여주고 있다. 두 변인 모두에서 시간, 조건 간에 차이는 없었다.

Melatonin level at hours of experiment at day 1 and 5 of each condition.

§ significantly different between day 1 and 5 at the same time period (p<.05).

* significantly different between conditions at the time period (p<.05).

논의

일주기리듬(circadian rhythm)은 일정한 시구간, 대략 24시간을 주기로 반복적으로 나타나는 생리적 리듬 현상을 말한다(Atkinson et al., 2007). 우선적으로 일주기 이동에 영향을 주는 자극 요인으로는 빛이 꼽히지만 운동 역시 주기이동에 주요한 조절자 역할을 한다. 이는 설치류와 인간모두에게서 나타난다(Atkinson et al., 2007; Baehr et al., 2003; Barger et al., 2004; Eastman et al., 1995; Edgar & Dement, 1991, Smith et al., 1992). 그리고 인간에게서 심야운동의 경우 일주기지연이 나타나며(Baehr et al., 2003; Barger et al., 2004; Eastman et al., 1995), 낮이나 오후의 운동은 주기를 단축시킨다고 보고되고 있다(Miyazaki et al., 2001; Yamanaka et al., 2010). 이러한 결과들은 운동 자극과 운동시간대가 주기이동과 그 향방에 역할을 한다는 것을 말해준다. 그러나 운동이 대사작용과 내분비계의 활성화 자극뿐 아니라 결과적으로 체온의 일주기에도 변화를 유도한다면 운동은 그 자체로 다양한 자극요인을 가진 것과 다름없게 된다. 게다가 운동이라는 자극의 어떠한 속성이 주기이동을 자극하는지에 대해 명확하지는 않다.

본 연구는 운동 중 발생할 수 있는 체온변화를 인위적으로 조절하였을 경우 심야운동이 일주기지연에 어떠한 영향을 미치는지 알아보고자 하였다. 운동 자극 변인을 고정하고 체온 변인을 변화시켜 그 효과를 관찰한 결과 대상자들은 26℃ 환경에서 높은 평균체온을 나타냈으며 운동 후 체중의 감소량도 더 높게 나타났다. 결과적으로 두 조건 모두에서 멜라토닌의 분비량을 근거로 일주기지연이 나타났다(그림 3). 그러나 운동 중 체온상승이 허락된 26℃ 조건에서 더 확연한 일주기 이동이 나타났다. 최소한 멜라토닌 분비량을 근거로 보자면, 운동 중 체온의 상승이 일주기이동을 강화시켰으며, 이는 운동자극과 더불어 열부하 자극이 추가적으로 작용했다는 것으로 해석된다. 이전의 연구들에서는 운동이 일주기를 이동시키는 것으로 결론을 맺고 있지만 운동으로 인한 열부하가 추가적으로 작용했다는 것에 대해 언급한 연구는 없었다.

본 연구에 참여한 피험자들은 두 심야운동 조건에서 서로 다른 생리적 반응을 보였다. 그럼에도 심부온은 두 조건 간에 차이를 나타내지 않았다. 인체는 대략적으로 세 개의 열수용체(thermoreceptor)가 존재하는 것으로 알려진다. 열조절기관인 시상하부가 하나이며, 척수, 내장 및 대정맥과 같은 심부수용체가 하나이고, 피부 및 말초부위의 피부감각기관들이 마지막 하나이다. 일반적으로 심부온도수용체가 감지하는 온도변화와 상태가 피부온도수용체에 비해 체온조절기능에 더욱 강력하게 작용한다. 본 연구는 실제로 심부온의 명확한 자극이 보이지 않음에도 피부온과 평균체온으로 평가되는 열부하가 충분히 열적 자극제가 되었음을 보여준다. 또는 이와는 달리 인체의 열함량으로 평가될 수 있는 총열량이 열자극의 평가 기준이 될 수 있음을 의미한다.

운동으로 발생한 근육의 움직임과 생리적 활성화가 체온상승과 함께 멜라토닌의 농도에 영향을 미치는 것으로 나타났지만, 최근의 연구에서 멜라토닌의 일주기는 주로 빛에 의해 관장되는 것에 반해 수면 일주기는 신체적 운동이나 일과에 의해 조절되는 것으로 보고되었다(Yamanaka et al., 2014). 이 연구의 결과에 근거하면 멜라토닌의 주기이동과 수면주기의 이동은 서로 다른 요인에 의해 조정된다는 것이다. 다시 말해 멜라토닌을 분비시키는 자극과 수면의 주기를 관장하는 자극이 서로 다를 수 있다는 것이다. 본 연구에서는 일주기의 모든 요인들이 이동했는가 또는 두 조건 간에 서로 다르게 일주기의 이동을 유발했는가는 확연치 않다. 다만 빛과 일과에서의 모든 사회적 신호가 동일하게 부여되었으며, 피험자들이 수면에 불만이 있었거나 불면증을 호소하지는 않았다. 운동요인과 체온요인을 분리시켜 결과를 관찰했을 때 이 요인들이 내분비의 주기를 변화시키는지 수면의 주기 변화를 유도하는지는 추후에 평가될 사항이다.

시상하부의 전면에 위치한 한 쌍의 시각교차위핵(suprachiasmatic nuclei; SCN)은 인체의 일주기를 조절하는 중요한 부위이며 SCN은 몇 가지 인자의 일주기 비동시성 리듬을 만들게 된다(Ralph et al., 1990). 인간의 일주기 이동을 유발하는 강력한 인자는 빛과 어둠이며, 빛은 망막시상하부 경로를 따라 빛의 정보를 이동시켜 SCN을 자극하게 된다. 그리고 빛에 의한 동조가 발현되어 송과체로부터 멜라토닌의 분비를 억제시킨다(Atkinson et al., 2007). 빛의 제한으로 분비되는 멜라토닌은 세로토닌의 전구체로 수면을 조절하는 역할을 수행하며 따라서 심야에 더욱 많은 양이 분비된다(Scheer & Czeisler, 2005). 동시에 체온은 점차로 낮아져 수면에서 깨기 전까지 최저점으로 향하게 된다(Atkinson & Reily, 1996). 체온은 새벽 2시를 전후로 약간 감소하게 되는데, 이 시간대에 운동을 실시함으로써 체온의 감소를 무마시키면서 멜라토닌 분비를 감소시켜 일주기를 지연하는 전략을 구사하였다. 이번 연구를 통해 심야운동은 03:30 시 멜라토닌의 수치를 낮추었으며, 반대로 정오시간의 수치는 상승시켰다. 그리고 두 조건 간에 분비량의 차이가 관찰되어 체온상승을 동반한 운동이 지연을 강화시킨 것으로 보인다.

일주기이동과 관련된 연구들은 이동의 지표로써 멜라토닌 이외에 코티졸과 갑상선자극호르몬의 수치나 체온의 반응을 관찰하게 된다. 이 변인들은 신경내분비계의 변화 즉 SCN의 변화를 살피는 지표로 사용되기 때문이다. 운동에 의한 급성 시상하부-뇌하수체-부신 축에 대한 반응을 통합적으로 살피는 과정이다. 심야운동이 타액의 코티졸 분비량 변화와 S-IgA 수준을 변화시키는지를 살펴본 것은 체온반응의 변화를 유도한 심야운동이 스트레스 상태와 염증지표에 어떠한 영향을 미쳤는지를 살펴보기 위함이었다. 결과적으로 두 실험중재 간에 차이가 나타나지 않았으며, 혈액에서 분석한 멜라토닌과는 달리 타액에서의 추출이 결과에 영향을 미쳤을 수도 있다. 그럼에도 두 조건 간에 차이가 나타나지 않은 것은 심야운동에서의 체온변화가 면역체계와 생리적 스트레스에 차별을 두지 않고 있음을 나타내고 있다.

심야운동 중 체온의 변이가 체중변화에 차이를 유발하였다. 심야운동은 체온상승의 조건에서 더 큰 체중감소를 보였다. 이를 반영하듯, 통계적으로는 유의하지 않았으나, 체온상승의 조건에서 심박수는 높은, 반대로 노배출량은 낮은 경향을 보였다. 체액량의 변화가 일주기변화에 영향을 미치는지에 대해서는 알려진 바는 없다. 본 연구에서는 극단적인 냉각의 효과로 인한 체액량의 변화를 최소화 시키고자 하였으며, 최소한 관찰된 결과들이 체액량의 변화폭에 의한 것은 아닌듯하다.

본 연구는 건강한 젊은 청년에게서 심야운동 중 체온의 변동을 유발한 경우 일주기이동에 어떠한 영향을 미치는지 알아보고자 했다. 운동이라는 자극을 근육의 활성화와 체온의 변화로 구분지어 체온만을 변화시키는 것이 일주기지연의 양태에 영향을 미칠 것인지를 평가한 것이다. 결과적으로 두 조건 모두에서 심야운동이 일주기지연을 유발하였다. 그러나 체온상승이 허락된 운동에서 일주기지연이 강화되었으며 이는 운동 중 발생하는 열부하가 일주기이동에 추가적으로 작용했음을 지적한다.

References

Aschoff, J., Fatranska, M., Giedke, H., Doerr, P., Stamm, D., & Wisser, H. (1971). Human circadian rhythms in continuous darkness: entrainment by social cures. Science, 171, 213-215.

Aschoff J., Fatranska M., Giedke H., Doerr P., Stamm D., et al, Wisser H.. 1971;Human circadian rhythms in continuous darkness: entrainment by social cures. Science 171:213–215. 10.1126/science.171.3967.213.Atkinson, G.. & Reilly, T. (1996). Circadian variation in sports performance. Sports Medicine, 21(4), 292-312.

Atkinson G., et al, Reilly T.. 1996;Circadian variation in sports performance. Sports Medicine 21(4):292–312. 10.2165/00007256-199621040-00005.Atkinson, G., Edwards, B., Reilly, T., & Waterhouse, J. (2007). Exercise as a synchroniser of human circadian rhythms: an update and discussion of the methodological problems. European Journal of Applied Physiology, 99, 331-341.

. Atkinson G., Edwards B., Reilly T., et al, Waterhouse J.. 2007;Exercise as a synchroniser of human circadian rhythms: an update and discussion of the methodological problems. European Journal of Applied Physiology 99:331–341. 10.1007/s00421-006-0361-z.Baehr, E. K., Eastman, C. I., Revelle, W., Olson, S. H. L., Wolfe, L. F., & Zee, P. C. (2003). Circadian phase-shifting effects of nocturnal exercise in older compared with young adults. American Journal of Physiology - Regulatory, Integrative and Comparative Physiology, 284, R1542-1550.

Baehr E. K., Eastman C. I., Revelle W., Olson S. H. L., Wolfe L. F., et al, Zee P. C.. 2003;Circadian phase-shifting effects of nocturnal exercise in older compared with young adults. American Journal of Physiology - Regulatory, Integrative and Comparative Physiology 284:R1542–1550. 10.1152/ajpregu.00761.2002.Barger, L. K., Wright, K. P., Hughes, R. J., & Czeisler, C. A. (2004). Daily exercise facilitates phase delays of circadian melatonin rhythm in very dim light. American Journal of Physiology - Regulatory, Integrative and Comparative Physiology, 286, R1077-1084.

Barger L. K., Wright K. P., Hughes R. J., et al, Czeisler C. A.. 2004;Daily exercise facilitates phase delays of circadian melatonin rhythm in very dim light. American Journal of Physiology - Regulatory, Integrative and Comparative Physiology 286:R1077–1084. 10.1152/ajpregu.00397.2003.Buxton, O. M., Frank, S. A., L'Hermite-Balériaux, M., Leproult, R., Turek, F. W., & Van Cauter, E. (1997). Roles of intensity and duration of nocturnal exercise in causing phase delays of human circadian rhythms. American Journal of Physiology, 273(3 Pt 1), E536-542.

. Buxton O. M., Frank S. A., L'Hermite-Balériaux M., Leproult R., Turek F. W., et al, Van Cauter E.. 1997;Roles of intensity and duration of nocturnal exercise in causing phase delays of human circadian rhythms. American Journal of Physiology 273(3 Pt 1):E536–542.Buxton, O. M., Lee, C. W., L'Hermite-Baleriaux, M., Turek, F. W., & Van Cauter, E. (2003). Exercise elicits phase shifts and acute alterations of melatonin that vary with circadian phase. American Journal of Physiology - Regulatory, Integrative and Comparative Physiology, 284, R714-724.

Buxton O. M., Lee C. W., L'Hermite-Baleriaux M., Turek F. W., et al, Van Cauter E.. 2003;Exercise elicits phase shifts and acute alterations of melatonin that vary with circadian phase. American Journal of Physiology - Regulatory, Integrative and Comparative Physiology 284:R714–724. 10.1152/ajpregu.00355.2002.Eastman, C. I., Hoese, E. K., Youngstedt, S. D., & Liu, L. (1995). Phase-shifting human circadian rhythms with exercise during the night shift. Physiology and Behavior, 58, 1287-1291.

Eastman C. I., Hoese E. K., Youngstedt S. D., et al, Liu L.. 1995;Phase-shifting human circadian rhythms with exercise during the night shift. Physiology and Behavior 58:1287–1291. 10.1016/0031-9384(95)02031-4.Edgar, D. M. & Dement, W. C. (1991). Regularly scheduled voluntary exercise synchronizes the mouse circadian clock. American Journal of Physiology, 261(4 Pt 2): R928-933.

Edgar D. M., et al, Dement W. C.. 1991;Regularly scheduled voluntary exercise synchronizes the mouse circadian clock. American Journal of Physiology 261(4 Pt 2):R928–933. 10.1152/ajpregu.1991.261.4.r928.Ellis, G. B., McKlveen, R. E., & Turek, F. W. (1982). Dark pulses affect the circadian rhythm of activity in hamsters kept in constant light. American Journal of Physiology - Regulatory, Integrative and Comparative Physiology, 242, R44-50.

Ellis G. B., McKlveen R. E., et al, Turek F. W.. 1982;Dark pulses affect the circadian rhythm of activity in hamsters kept in constant light. American Journal of Physiology - Regulatory, Integrative and Comparative Physiology 242:R44–50. 10.1152/ajpregu.1982.242.1.r44.Goel, N. (2005). Late-night presentation of an auditory stimulus phase delays human circadian rhythms. American Journal of Physiology - Regulatory, Integrative and Comparative Physiology, 289, R209-216.

Goel N.. 2005;Late-night presentation of an auditory stimulus phase delays human circadian rhythms. American Journal of Physiology - Regulatory, Integrative and Comparative Physiology 289:R209–216. 10.1152/ajpregu.00754.2004.Hack, L. M., Lockley, S. W., Arendt, J., & Skene, D. J. (2003). The effects of low-dose 0.5 mg melatonin on the free-running circadian rhythms of blind subjects. Journal of Biological Rhythms, 18, 420-429.

Hack L. M., Lockley S. W., Arendt J., et al, Skene D. J.. 2003;The effects of low-dose 0.5 mg melatonin on the free-running circadian rhythms of blind subjects. Journal of Biological Rhythms 18:420–429. 10.1177/0748730403256796.Heyward, V. H. (2006). Advanced Fitness Assessment and Exercise Prescription(5th ed). IL:Human Kinetics.

Heyward V. H.. 2006. Advanced Fitness Assessment and Exercise Prescription 5th edth ed. IL: Human Kinetics. 10.1249/00005768-199202000-00023.Jackson, A. S., & Pollock, M. L. (1978). Generalized equations for predicting body density of men. British Journal of Nutrition, 40, 497-504.

Jackson A. S., et al, Pollock M. L.. 1978;Generalized equations for predicting body density of men. British Journal of Nutrition 40:497–504. 10.1079/bjn19780152.Lewy, A. J., Bauer, V. K., Ahmed, S., Thomas, K. H., Cutler, N. L., Singer, C. M., Moffit, M. T., & Sack, R. L. (1998). The human phase response curve (PRC) to melatonin is about 12 hours out of phase with the PRC to light. Chronobiology International, 15, 71-83.

Lewy A. J., Bauer V. K., Ahmed S., Thomas K. H., Cutler N. L., Singer C. M., Moffit M. T., et al, Sack R. L.. 1998;The human phase response curve (PRC) to melatonin is about 12 hours out of phase with the PRC to light. Chronobiology International 15:71–83. 10.3109/07420529808998671.Miyazaki, T., Hashimoto, S., Masubuchi, S., Honma, S., & Honma, K. I. (2001). Phase-advance shifts of human circadian pacemaker are accelerated by daytime physical exercise. American Journal of Physiology - Regulatory, Integrative and Comparative Physiology, 281, R197-205.

Miyazaki T., Hashimoto S., Masubuchi S., Honma S., et al, Honma K. I.. 2001;Phase-advance shifts of human circadian pacemaker are accelerated by daytime physical exercise. American Journal of Physiology - Regulatory, Integrative and Comparative Physiology 281:R197–205. 10.1152/ajpregu.2001.281.1.r197.Monteleone, P., Fuschino, A., Nolfe, G., Maj, M. (1992). Temporal relationship between melatonin and cortisol responses to nighttime physical stress in humans. Psychoneuroendocrinology, 17(1), 81-86.

Monteleone P., Fuschino A., Nolfe G., Maj M.. 1992;Temporal relationship between melatonin and cortisol responses to nighttime physical stress in humans. Psychoneuroendocrinology 17(1):81–86. 10.1016/0306-4530(92)90078-l.Ralph, M. R., Foster, R. G., Davis, F. C., & Menaker, M. (1990). Transplanted suprachiasmatic nucleus determines circadian period. Science, 247(4945), 975-978.

Ralph M. R., Foster R. G., Davis F. C., et al, Menaker M.. 1990;Transplanted suprachiasmatic nucleus determines circadian period. Science 247(4945):975–978. 10.1126/science.2305266.Reebs, S. G., & Mrosovsky, N. (1989). Effects of induced wheel running on the circadian activity rhythms of Syrian hamsters: entrainment and phase response curve. Journal of Biological Rhythms, 4, 39-48.

Reebs S. G., et al, Mrosovsky N.. 1989;Effects of induced wheel running on the circadian activity rhythms of Syrian hamsters: entrainment and phase response curve. Journal of Biological Rhythms 4:39–48. 10.1177/074873048900400103.Roberts, M. F., Wenger, C. B., Stolwijk, J. A., & Nadel, E. R. (1977). Skin blood flow and sweating changes following exercise training and heat acclimation. Journal of Applied Physiology, 43, 133-137.

. Roberts M. F., Wenger C. B., Stolwijk J. A., et al, Nadel E. R.. 1977;Skin blood flow and sweating changes following exercise training and heat acclimation. Journal of Applied Physiology 43:133–137. 10.1152/jappl.1977.43.1.133.Scheer, F. A., & Czeisler, C. A. (2005). Melatonin, sleep, and circadian rhythms. Sleep Medicine Reviews, 9(1), 5-9.

Scheer F. A., et al, Czeisler C. A.. 2005;Melatonin, sleep, and circadian rhythms. Sleep Medicine Reviews 9(1):5–9. 10.1016/j.smrv.2004.11.004.Shanahan, T. L., Kronauer, R. E., Duffy, J. F., Williams, G. H., & Czeisler, C. A. (1999). Melatonin rhythm observed throughout a three-cycle bright-light stimulus designed to reset the human circadian pacemaker. Journal of Biological Rhythms, 14, 237-253.

Shanahan T. L., Kronauer R. E., Duffy J. F., Williams G. H., et al, Czeisler C. A.. 1999;Melatonin rhythm observed throughout a three-cycle bright-light stimulus designed to reset the human circadian pacemaker. Journal of Biological Rhythms 14:237–253. 10.1177/074873099129000560.Smith, R. D., Turek, F. W., & Takahashi, J. S. (1992). Two families of phase-response curves characterize the resetting of the hamster circadian clock. American Journal of Physiology, 262, R1149-1153.

. Smith R. D., Turek F. W., et al, Takahashi J. S.. 1992;Two families of phase-response curves characterize the resetting of the hamster circadian clock. American Journal of Physiology 262:R1149–1153. 10.1152/ajpregu.1992.262.6.r1149.Smoak, B., Deuster, P., Rabin, D., & Chrousos, G. (1991). Corticotropin-releasing hormone is not the sole factor mediating exercise-induced adrenocorticotropin release in humans. The Journal of clinical endocrinology and metabolism, 73(2), 302-306.

Smoak B., Deuster P., Rabin D., et al, Chrousos G.. 1991;Corticotropin-releasing hormone is not the sole factor mediating exercise-induced adrenocorticotropin release in humans. The Journal of clinical endocrinology and metabolism 73(2):302–306. 10.1210/jcem-73-2-302.Turek, F. W. (1989). Effects of stimulated physical activity on the circadian pacemaker of vertebrates. Journal of Biological Rhythms, 4, 135-148.

Turek F. W.. 1989;Effects of stimulated physical activity on the circadian pacemaker of vertebrates. Journal of Biological Rhythms 4:135–148. 10.1177/074873048900400204.Vallerand, A. L., & Jacobs, I. (1989). Rates of energy substrates utilization during human cold exposure. European journal of applied physiology and occupational physiology, 58, 873-878.

Vallerand A. L., et al, Jacobs I.. 1989;Rates of energy substrates utilization during human cold exposure. European journal of applied physiology and occupational physiology 58:873–878. 10.1007/bf02332221.Van Reeth, O., Sturis, J., Byrne, M. M., Blackman, J. D., L'Hermite-Baleriaux, M., Leproult, R., Oliner, C., Refetoff, S., Turek, F. W., & Van Cauter, E. (1994). Nocturnal exercise phase delays circadian rhythms of melatonin and thyrotropin in normal men. American Journal of Physiology - Endocrinology and Metabolism, 266, E964-974.

Van Reeth O., Sturis J., Byrne M. M., Blackman J. D., L'Hermite-Baleriaux M., Leproult R., Oliner C., Refetoff S., Turek F. W., et al, Van Cauter E.. 1994;Nocturnal exercise phase delays circadian rhythms of melatonin and thyrotropin in normal men. American Journal of Physiology - Endocrinology and Metabolism 266:E964–974.Wickland, C. R., & Turek, F. W. (1991). Phase-shifting effects of acute increases in activity on circadian locomotor rhythms in hamsters. American Journal of Physiology - Regulatory, Integrative and Comparative Physiology, 261, R1109-1117.

Wickland C. R., et al, Turek F. W.. 1991;Phase-shifting effects of acute increases in activity on circadian locomotor rhythms in hamsters. American Journal of Physiology - Regulatory, Integrative and Comparative Physiology 261:R1109–1117. 10.1152/ajpregu.1991.261.5.r1109.Yamanaka, Y., Hashimoto, S., Tanahashi, Y., Nishide, S. Y., Honma, S., & Honma, K. (2010). Physical exercise accelerates reentrainment of human sleep-wake cycle but not of plasma melatonin rhythm to 8-h phase-advanced sleep schedule. American Journal of Physiology - Regulatory, Integrative and Comparative Physiology, 298(3), R681-691.

. Yamanaka Y., Hashimoto S., Tanahashi Y., Nishide S. Y., Honma S., et al, Honma K.. 2010;Physical exercise accelerates reentrainment of human sleep-wake cycle but not of plasma melatonin rhythm to 8-h phase-advanced sleep schedule. American Journal of Physiology - Regulatory, Integrative and Comparative Physiology 298(3):R681–691.Yamanaka, Y., Hashimoto, S., Masubuchi, S., Natsubori, A., Nishide, S. Y., Honma, S., & Honma, K. I. (2014). Differential regulation of circadian melatonin rhythm and sleep-wake cycle by bright lights and non-photic time cues in humans. American Journal of Physiology - Regulatory, Integrative and Comparative Physiology, 2014 Jun 18. pii: ajpregu.00087.2014. [Epub ahead of print]

. Yamanaka Y., Hashimoto S., Masubuchi S., Natsubori A., Nishide S. Y., Honma S., et al, Honma K. I.. 2014;06. 18. Differential regulation of circadian melatonin rhythm and sleep-wake cycle by bright lights and non-photic time cues in humans. American Journal of Physiology - Regulatory, Integrative and Comparative Physiology pii: ajpregu. Epub ahead of print.